Author: Siti Shalima Nazrin

Introduction

From the era of Madonna to Harry Styles, the music industry has undergone shifts in distribution medium, going from CDs to streaming. Nowadays, the digitalization of the music industry allows you to play your favorite songs, in certain cases for free, with just one click away—thanks to the existence of streaming platforms such as Spotify, Apple Music, YouTube Music, and more.

The question is, how does the ever-evolving music industry affect us? In this writing, we seek to analyze its economic impacts on consumers, nations, and artists. Furthermore, the arguments and evidence presented in this writing will not be focused on a certain country, but rather on a global scope.

Development of the Music Industry

Dolota (2020) explained that the digital transformation of the music industry can be categorized into four phases. The first phase (1983-1999) marked the switch from vinyl to CD. The second phase (1999-2003) was marked by the emergence of music file-sharing platforms such as Napster. The third phase (2003-2013) was characterized by the opening of legal online music stores such as Apple iTunes and Spotify. Currently, we are in the third phase (2013-present) where music streaming is preferable to listening to physical copies (e.g. CD) of music.

The digitalization and continued digitization of the music industry has fostered many benefits for music listening—which will be elaborated on later in this paper. It has made music more convenient, encouraged legal streaming, and created an option to listen to music for free.

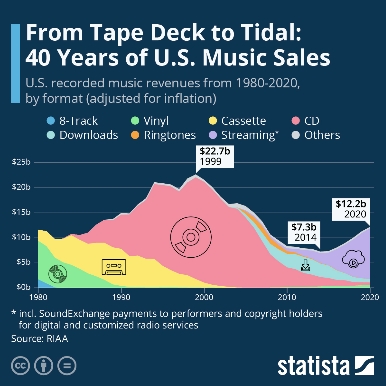

How Streaming Services Reduced Music Piracy

However, the digitalization of music was not always advantageous, and one of the main causes was music piracy. Just like an untreated virus can lead to a deteriorating body, music piracy can lead to a continuous decrease in music revenue. In the United States (US), the number of music sales was consistently sliding off from 1999 to 2010 (see Graph 1) and music piracy is to blame for it (Richter, 2021). Globally, the music market suffered a 40% decrease in retail revenues.

The harmful effects of piracy on music sales were made possible because of a handful of reasons. From a customer perspective, downloading music illegally for free on your iPods or mp3 players can be more tempting than having to pay for physical albums that can only be played with CD players. Besides price and portability factors, the music industry also lacked a quick development of an attractive legal streaming service. Evidently, Apple iTunes Music Store was developed in 2003, four years after the release date of Napster (Knopper, 2009). This gap allowed the market to become accustomed to listening to free illegal music, thus leading to a decrease in music sales in the US.

Graph 1. US Music Sales (Richter, 2021)

While the issue of piracy is timeless, the increasing growth of streaming services in the music industry acts as a solution to reduce and mitigate the said issue. As shown in Graph 1, in the US, the growth of music streaming sales was accompanied by a rapid increase in music revenues from $7.3B in 2014 to $12.2B in 2020. On the other side of the globe, the United Kingdom (UK) saw a similar phenomenon. The growth of the streaming industry was followed by a decrease in the piracy rate from 13% in 2014 to only 5% in 2020 (House of Commons, 2021). These statistics beg the question: why does the growth of music streaming lead to a decrease in piracy?

Even though there are many reasons why music streaming has become preferable for consumers compared to illegal music listening, this article will argue on the basis of two factors; increased consumer surplus and the network effect.

OECD Statistics Directorate (2002) defined consumer surplus as a measure of consumer welfare that equates to the excess of social valuation over the actual product price. In the music world, consumer surplus is the gap between the price of a song and a consumer’s willingness to pay for the song.

Since the rise of music streaming, studies have shown that consumer surplus also rose. Equist, Goodridge, and Haskel (2021) have found that in the US, the shift from CD to streaming has resulted in a price decrease of 85% per song. From this decrease, US consumers approximately derive a $1B annual consumer surplus (Brynjolfsson, Hu, & Smith, 2003; Waldfogel, 2017).

The second explanation for the preferability of music streaming is due to the network effect. The network effect occurs when a streaming platform offers its additional services to steer consumers towards complementary goods and services (Towse, 2020). For instance, streaming services that offer a free listening option such as Spotify and Pandora tend to promote their subscription packages to their users. This subscription is usually accompanied by a distinguishing feature that makes it better than the free package, for instance, no advertisements and no limitations on the number of “skips”. Thus, even though users have to pay for a subscription, their experience will also be enhanced because they have received an added value. Going back to why streaming is preferable to illegal music sites, these added values are usually nonexistent on illegal music sites which is precisely why streaming services are preferable.

How Streaming Makes Music Production More Affordable

Besides reducing piracy, the rise of streaming services has also reduced the cost of music production for artists. Waldfogel (2015) states that for only about $10, an artist can make their song available on iTunes. In comparison, the cost of producing music before the era of music streaming was roughly around $1M per album for a new artist, which is equivalent to $100,000 per song if an album contains 10 songs (Vogel, 2007).

The cost difference of producing music between pre-streaming (hereinafter referred to as the traditional model) and during the streaming era, lies in the difference in the cost per process. The International Federation of the Phonographic Industries (2010) explains that the traditional model follows three key steps. Firstly, a record label identifies a promising talent to sign into their label. For example, in 2008, Scooter Braun from RMBG Records discovered Justin Bieber on YouTube and signed him to the label (CNN, 2019). Second, the record label will invest in producing the artist’s music using professional and expensive equipment. Lastly, the record label will begin producing music videos and other promotional content, as well as distributing physical albums.

With free computer software for editing music and inexpensive equipment, Waldfogel (2017) argues that the cost of producing music is becoming more affordable than ever. Moreover, the emergence of streaming services also helps independent artists—artists who are not signed by any record labels—to make their music available on streaming platforms such as Spotify and Apple Music in licensing, distribution, and administration processes (Spotify for Artists, 2022; Apple Music for Artists, 2022).

The Cost of Streaming: Is Streaming a Modern-Day Slavery?

Despite the growth of the streaming industry and the benefits that come with it, profit-share remains a concern for artists all over the world. In 2020, the American rapper Kanye West voiced his concern about the lack of profit he made from Spotify. With 14-25% of royalties not being received at the time, West claimed that Spotify was “modern-day slavery” (Laker, 2021). Furthermore, artists in the UK and Norway seem to be having the same problem. Even though music revenue in the UK in 2020 reached £1B, artists were only paid as little as 13% of the revenue. In Norway, despite the growth of music streaming from 5% in 2011 to 14% in 2017, physical sales fell from 10% to 9% and the share of composers and performers fell from 29% to 24% (The Norwegian Ministry of Culture, 2019). Hence, why do streaming services pay so little to their artists?

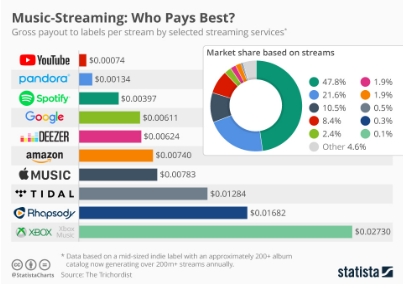

Graph 2. Payout comparison per streaming platform (Wagner, 2018)

Before considering the determinants of payout per stream, it is important to note that the amount of money paid from a streaming service to its artists may differ because each platform has its own systems. For example, Graph 1 shows that YouTube Music pays as little as $0.00074/stream, Spotify pays $0.0097/stream, while Apple Music pays as much as $0.00783/stream.

Towse (2017) explains that streaming revenue (payout per stream) is influenced by the streaming platform’s main source of income; subscription fees and advertisement fees. The amount of money that a streaming platform gets from subscription fees depends on the price it sets for a subscription package. To set the price, streaming platforms will analyze the market’s willingness to pay based on the data they have of their users such as but not limited to gender, age, and interests (Ezrachi and Stucke, 2019). Because the user demography of each streaming platform may differ, so will their willingness to pay, hence the variety of subscription fees.

Income from advertisement fees can also be crucial for streaming platforms that offer an ad-supported free listening option, such as Spotify and YouTube Music. To compensate for the loss of subscription fees from the free listening option, Spotify and YouTube Music facilitate companies who want to put advertisements and charge them for it. This is reflected in YouTube Music’s payout scheme which includes three types of payouts, one of which is a monetization payout of $0.00087/stream (Kormoczi, 2020).

Thus, it can be concluded that the factors that influence the amount of stream payout to artists are different systems, subscription fees, and advertisement fees.

Conclusion

In conclusion, the digitalization and continued digitization of the music industry has birthed the rise of streaming services, which has brought both benefits and costs. On the positive side, streaming services have reduced piracy, increased consumer surplus, improve the consumer experience, and reduced the cost of music production. On the negative side, revenues for artists from streaming services still remain a concern. In this essay, we have discussed the determinants of the amount of revenue. However, due to limited data, further research is advised to recommend a concrete solution to address the revenue concern.

Bibliography

Apple Music for Artists. (2022). Get your music on apple music. Retrieved April 23, 2022, from https://artists.apple.com/support/1108-get-your-next-release-on-apple-music

Brynjolfsson, E., Hu, Y. (., & Smith, M. D. (2003). Consumer Surplus in the digital economy: Estimating the value of increased product variety at online booksellers. Management Science, 49(11), 1580-1596. doi:10.1287/mnsc.49.11.1580.20580

CNN (2019, September 03). Justin Bieber: From YouTube to global superstar. Retrieved April 23, 2022, from https://edition.cnn.com/2019/03/26/entertainment/gallery/justin-bieber/index.html

Dolata, U. (2020). The Digital Transformation of the Music Industry. The Second Decade: From Download to Streaming. Retrieved April 23, 2022, from http://hdl.handle.net/10419/225509

Edquist, H., Goodridge, P., & Haskel, J. (2021). The economic impact of streaming beyond GDP. Applied Economics Letters, 29(5), 403-408. doi:10.1080/13504851.2020.1869158

Ezrachi, A., & Stucke, M. E. (2019). Virtual competition: The promise and perils of the algorithm-driven economy. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

House of Commons (2021, July 15) Economics of music streaming Second Report of Session 2021-22. https://committees.parliament.uk/publications/6739/documents/72525/default/

International Federation of the Phonographic Industry (IFPI) (2010). Investing in Music: How Music Companies Discover, Develop, and Promote Talent. https://ifpi.at/website2018/wp-content/uploads/2018/12/investing-in-music.pdf

Knopper, S. (2009). Appetite for self-destruction: The spectacular crash of the record industry in the Digital Age. Steve Knopper.

Kormoczi, R. (2020, October 28). How much can an artist earn with YouTube music? Retrieved April 23, 2022, from https://timesinternational.net/how-much-can-an-artist-earn-with-youtube-music/

Laker, B. (2021, December 10). The Economics Of Music Streaming And The Role Of Music Streaming Platforms. Forbes. https://www.forbes.com/sites/benjaminlaker/2020/10/28/heres-how-lockdown-has-shown-that-spotify-has-a-sustainability-problem/?sh=7ad7c161599b

The Norwegian Ministry of Culture. (2019, October 22). What now – The Impact of Digitization on the Norwegian Music Industry. Government.no; Government.no. https://www.regjeringen.no/en/dokumenter/what-now—the-impact-of-digitization-on-the-norwegian-music-industry/id2627950/

OECD Statistics Directorate. (2002). OECD Glossary of Statistical Terms – Consumers’ surplus Definition. OECD. https://stats.oecd.org/glossary/detail.asp?ID=3176#:~:text=Consumers’%20surplus%20is%20a%20measure,and%20above%20the%20observed%20price.

Richter, F. (2021, March 5). Infographic: From Tape Deck to Tidal: 40 Years of U.S. Music Sales. Statista Infographics; Statista. https://www.statista.com/chart/17244/us-music-revenue-by-format/

Spotify for Artists. (2022). Help – Getting music on Spotify. Retrieved April 23, 2022, from https://artists.spotify.com/help/article/getting-music-on-spotify?category=getting-started

Towse, R. (2020). Dealing with digital: The Economic Organisation of streamed music. Media, Culture & Society, 42(7-8), 1461-1478. doi:10.1177/016344372091937

Wagner, P. (2018, April 3). Music-Streaming: Who Pays Best? Statista Infographics; Statista. Retrieved April 23, 2022, from https://www.statista.com/chart/13407/music-streaming_-who-pays-best/

Waldfogel, J. (2015). Digitization and the Quality of New Media Products (A. Goldfarb, S. M. Greenstein, & C. E. Tucker, Eds.). Economic Analysis of the Digital Economy, 407-442. doi:10.7208/chicago/9780226206981.003.0014

Waldfogel, J. (2017). How Digitization Has Created a Golden Age of Music, Movies, Books, and Television. The Journal of Economic Perspectives, 31(3), 195–214. http://www.jstor.org/stable/44321286

Vogel, H. (2007). Entertainment Industry Economics: A Guide for Financial Analysis (7th ed.). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. doi:10.1017/CBO9780511510786