Author: Muhammad Farel Juniska Amansyah

Supervisor: Dicky Agung Prasetyo

Understanding Recession: Conservative Consumption in Uncertain Times

A general decline in the economy is referred to as a recession, a period when the entire economic chain is disrupted due to a market downturn. While the causes may vary from one recession to another, one consistent outcome remains: society becomes worse off. This is primarily because people’s purchasing power declines simultaneously with the broader economic contraction, leaving many with money that holds less and less value (Bitler & Hoynes, 2015).

In response to this threat, society tends to behave much more conservatively, especially in terms of spending. This behavior is driven by the unpredictable nature of the period, where people may suddenly lose their jobs due to a drop in production capacity or face another potential economic downturn in the near future (Griskevicius et al., 2013). As a result, in severe cases of recession, when market distrust reaches its peak, increasingly conservative spending can lead to a deeper recession, or even a depression (Ejarque, 2008).

Recession generally sounds like a nightmare, a time when society as a whole becomes worse off. However, there is a theory that suggests certain industry segments actually go against the current. These industries, instead of being worse off due to the situation, experience a relatively stable or even general increase in their sales. This phenomenon is called the lipstick effect, the anomaly of all. While this is more of a mere hypothesis, its interesting nature during economic downturns deserves further observation and statistical comparison to explore its validity.

The Lipstick Effect: From Luxury Substitution to Emotional Spending

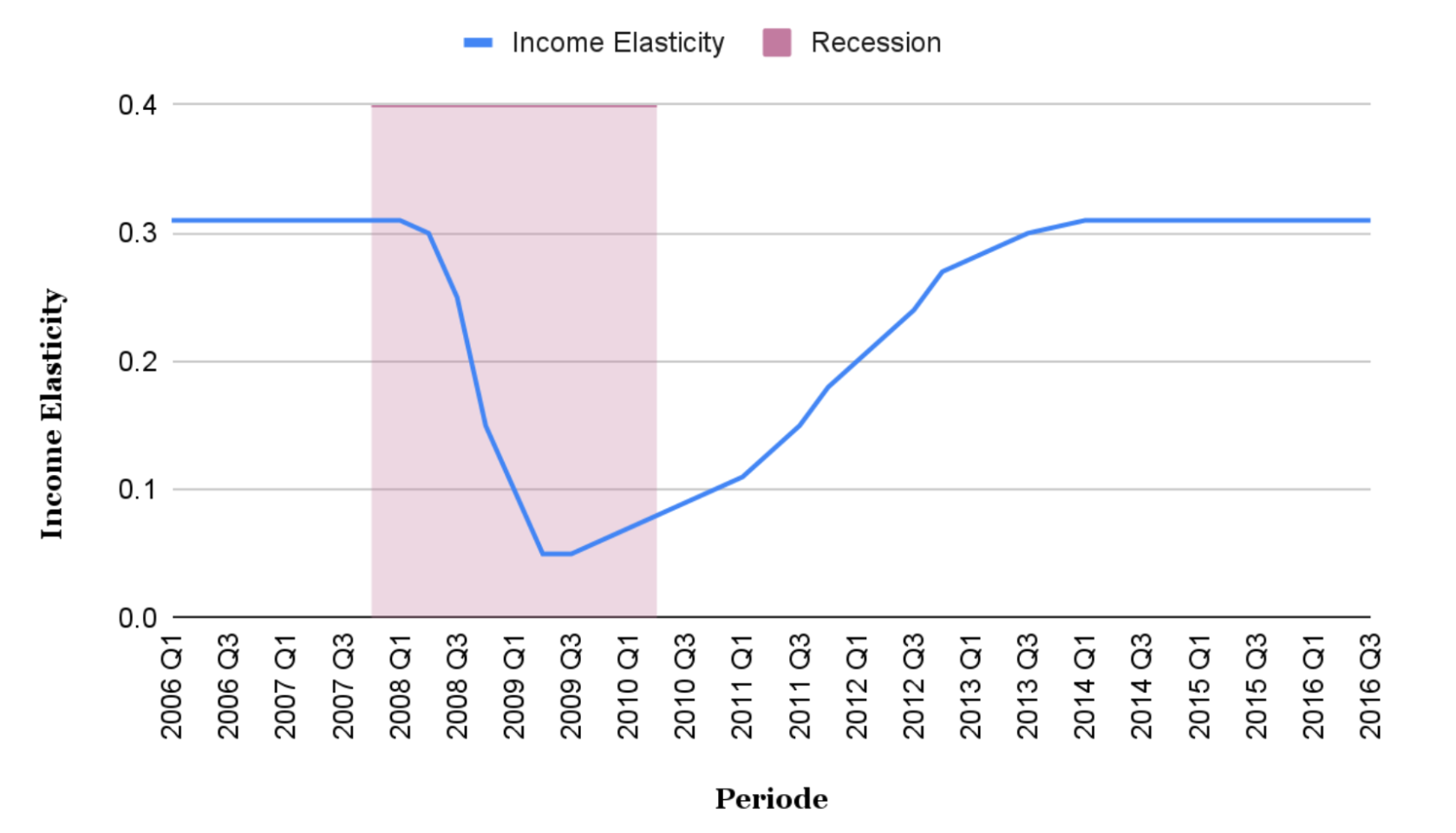

Figure 1. Income Elasticity of Lipstick During the 2007–2009 Recession

Source: Li et al. (2020), processed by author

The lipstick effect illustrates how consumers shift their spending toward small luxury items, such as cosmetics, during times of economic hardship. The term was first popularized by Leonard Lauder in the early 2000s, following his observation of sales trends at his luxury brand, Estée Lauder, after the 2001 terrorist attacks in the United States (Schaefer, 2008). He hypothesized, through what he called the “lipstick index”, that rising cosmetic sales during economic crises could serve as an indicator of financial downturns. Lauder later described the lipstick effect as a substitution of high-priced fashion items with luxury makeup products that are significantly more affordable during and after a crisis (Schaefer, 2008). Supporting this theory, Li et al. (2020) found that during the 2007-2009 recession, the income elasticity of demand for lipstick dropped from 0.31 to just 0.05, indicating relatively stable or even increasing consumption despite declining macroeconomic conditions.

In recent years, however, the definition of the lipstick effect has broadened. It is now not limited to an increase in cosmetic sales, but more broadly refers to any rise in spending on non-essential or small luxury goods during an economic downturn. This effect reflects how individuals substitute costly activities such as expensive vacations, new wardrobes, or fine dining with more affordable indulgences (Li et al., 2020). A relevant example of this trend can be seen in the rise of the homemade dalgona coffee trend, potentially a substitute for those who can’t afford tens-of-thousands-rupiah coffee. This indicates that the lipstick effect is not merely a tendency for individuals to maintain spending, but also a symbolic act of emotional relief, identity affirmation, and the pursuit of pleasure under pressure.

Beyond Economics: Psychological Drivers Behind the Lipstick Effect

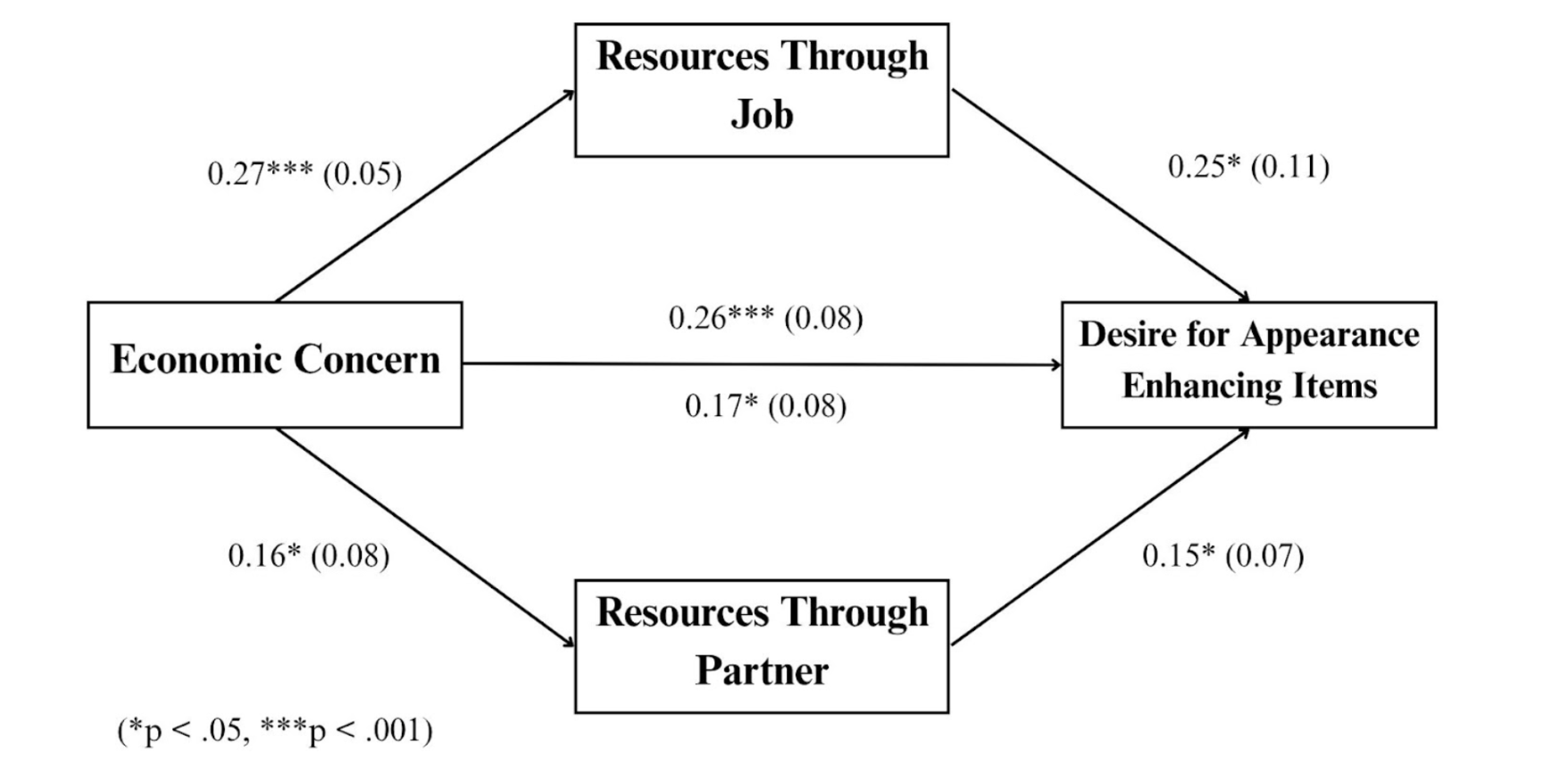

Figure 2. Effect of Economic Concern on the Desire for Appearance-Enhancing Items

Source: Netchaeva and Rees (2016), processed by author

Earlier theories of the lipstick effect, specifically those in Hill et al. (2012), suggest that one of the causes of the lipstick effect is the motivation to get a partner who is financially better off in times of crisis. Though this may be true, a newer finding from Netchaeva and Rees (2016) suggests that there are stronger incentives to purchase look-enhancing products, particularly the desire to create a better professional impression. According to Figure 2, additional economic concern during a recession contributes only b = 0.15 toward the motivation to seek romantic relationships, compared to b = 0.25 to enhance one’s appearance as a working woman. The b values represent standardized regression coefficients, where a larger value indicates a stronger influence on individual motivation. This is strongly influenced by professional performance evaluations, as women who wore professional looks (for example, contrasting eyeshadow and brighter lipstick) were perceived as more competent than those who did not (Etcoff et al., 2011, as cited in Netchaeva & Rees, 2016). Hence, enhancing their personal appearance is one strategy women may use to better secure their position in times of uncertainty.

While the trigger for the lipstick effect might stem from external factors, such as the desire to attract the opposite sex or to appear professional, it is also closely tied to personal emotional and psychological reactions, as observed during COVID-19 (Pusetti, 2023). In her study of 112 women, Pusetti found that women often seek control and emotional stability through small activities such as aromatherapy baths, hair care, self-yoga, and specifically, nature-based products. Additionally, Pusetti (2023) noted that due to the pandemic restrictions, which coincided with the last recession, the work-from-home culture provided women with a greater sense of freedom to engage in beauty procedures without time constraints. During this period, it became increasingly common to find home-service spa or Botox treatments, directly demonstrating how the market for women’s beauty is recession-proof and will not plummet (Pusetti, 2023).

This hypothesis is also supported by findings from MacDonald and Dildar (2020), who examined cosmetic purchasing behavior during the 2008-2010 recession. Their study revealed that makeup expenditures among married women increased by 9.8%, compared to a smaller 2.8% increase among unmarried women. Furthermore, the spending behavior of unmarried women remained relatively stable when compared to their consumption patterns prior to the recession. These results suggest that romantic motivations were not the primary driver of cosmetic purchases among single women during the economic downturn. Instead, the findings support the notion that cosmetic consumption may serve as a form of self-expression and emotional self-satisfaction for women during times of crisis (MacDonald & Dildar, 2020).

Contradicting the Trend: When Data Challenges the Lipstick Effect

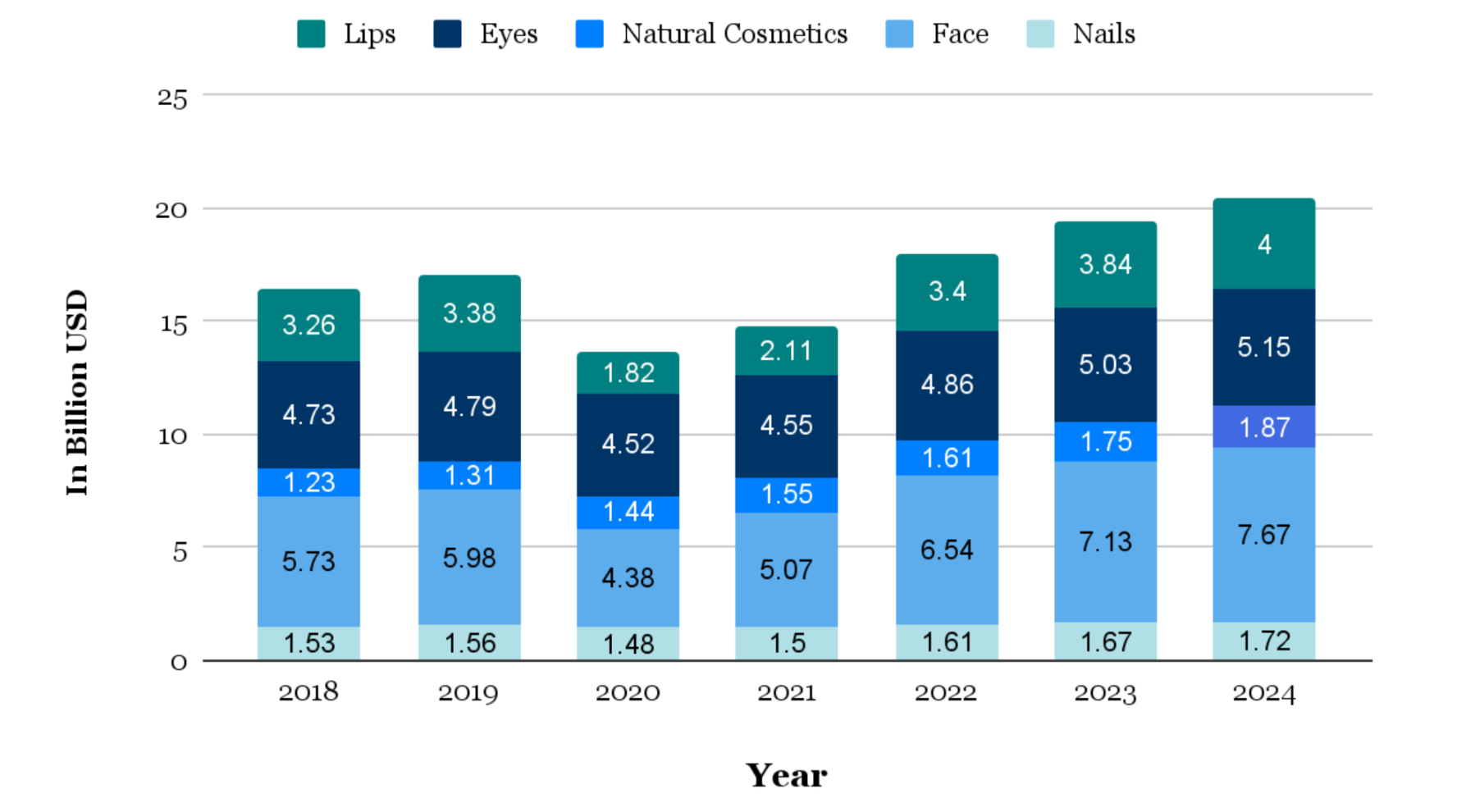

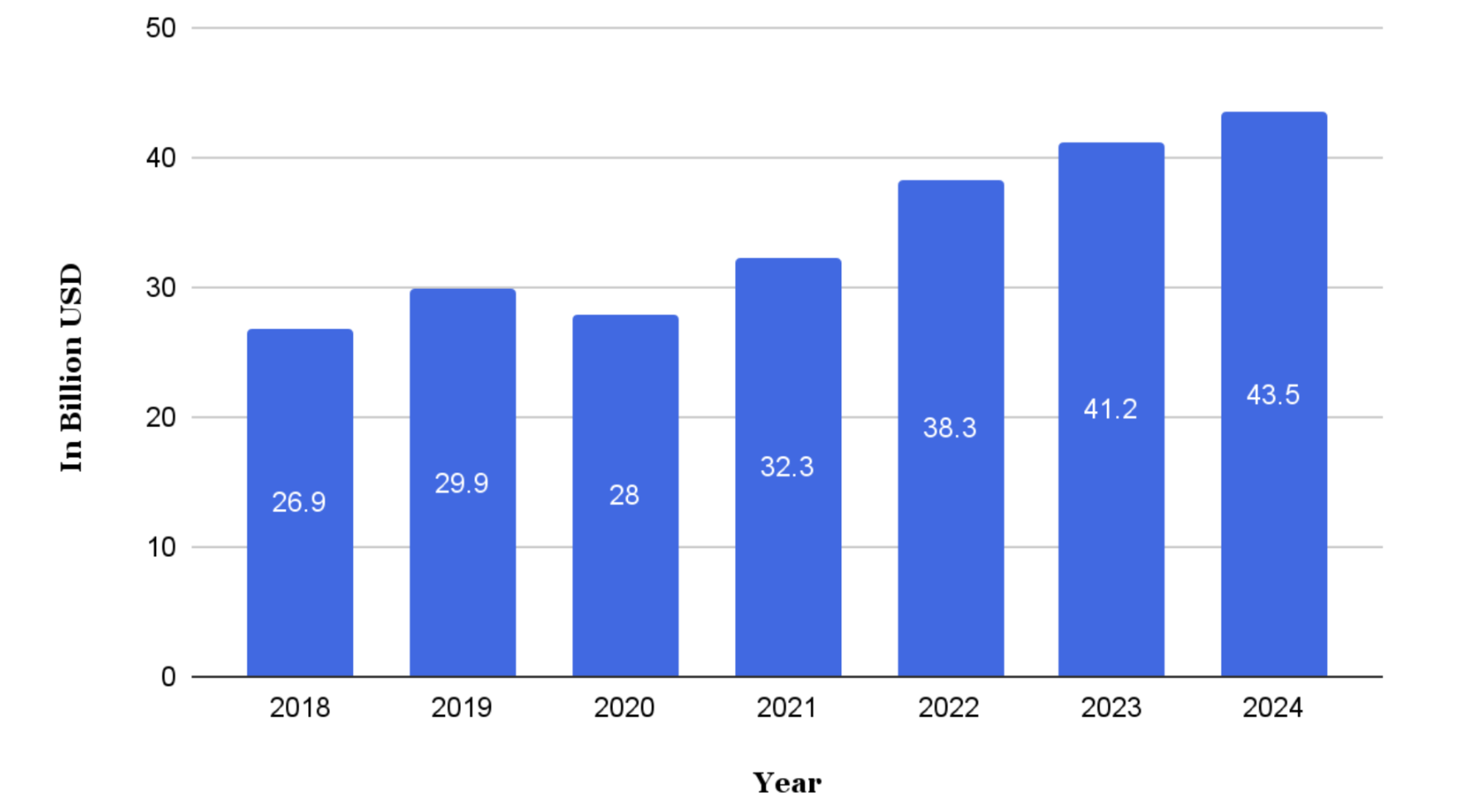

Figure 3. Cosmetic Market Revenue in the USA 2018-2024

Source: Statista (2025), processed by author

While the concept of a negative relationship between cosmetics sales and the economic state is interesting, most statistics to date suggest otherwise. Specifically, cosmetics sales in the USA decreased drastically in the year of crisis, notably in 2020, with a decline of almost a quarter (24.85%). The statistics reflect the market behaviour observed during the Covid-19 recession. This presents a notable contradiction of the hypothesis that cosmetics sales tend to increase during a crisis. Although there was a slight increase in natural cosmetics at the time, in line with Pusetti’s (2023) findings, the majority of the data indicates the opposite.

Figure 4. Cosmetics Market Revenue in the USA 2005-2014

Source: Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) Consumer Expenditure Survey Microdata, 2005–2014, cited in MacDonald & Dildar (2020), processed by author.

The same pattern is presented in Figure 4. It is observed that during the 2008 recession, cosmetics sales dropped, just as they did during the 2020 crisis. In comparison to the start of the crisis in 2007, there was a 12.96% decrease in cosmetic sales by 2010, raising a valid question: Is the lipstick effect in the cosmetics industry really happening? Is it just another theory that doesn’t manifest in real life? And if sales are indeed decreasing during an economic downturn, then there may be no special effect at all, as the industry is simply reacting normally to worsening economic conditions.

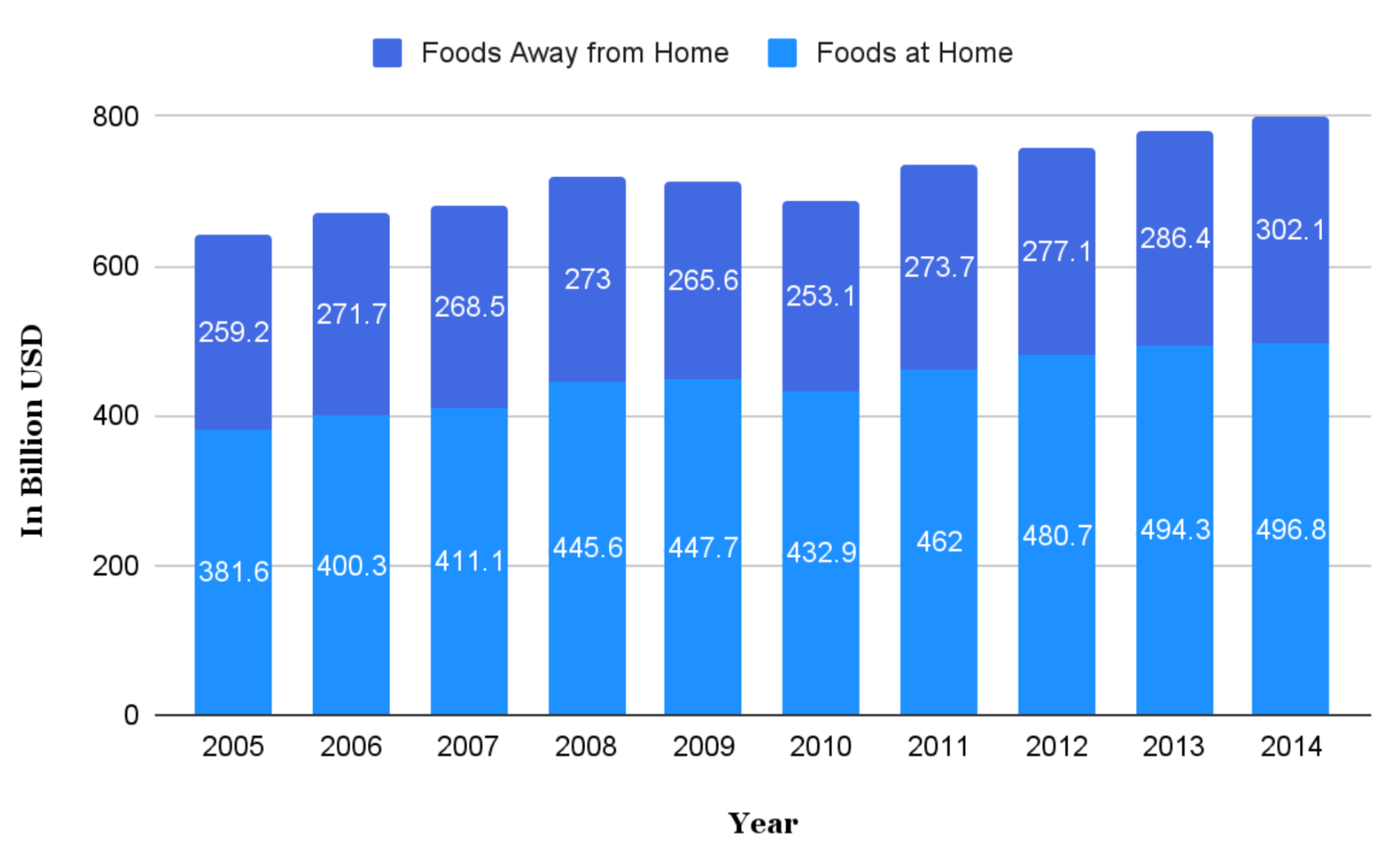

Figure 5. Consumer Expenditure on Food in the USA 2005-2014

Source: Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) Consumer Expenditure Survey Microdata, 2005–2014, cited in MacDonald & Dildar (2020), processed by author.

By the end, the negative relationship hypothesized by some studies seems to contradict its own claim. Figure 3 and Figure 4 clearly show a decline in cosmetics sales during times of crisis, highlighting a pattern of reduced consumption in the industry. Simultaneously, Figure 5 illustrates that consumer expenditure on food is much more recession-proof, with only a 6.08% drop from the start of the crisis to 2010. While consumer expenditure seems to be much more stable (Figure 5), these findings all suggest a positive relationship, where a decline in economic conditions leads to a decrease in consumption across society. This raises many questions about the validity of the theory in real-world scenarios, especially since even primary goods appear to react normally to a crisis.

Figure 6. L’Oréal Revenue Worldwide 2

018-2024

Source: L’Oréal Finance (2025), processed by author

While the contradiction of the lipstick effect theory is observed in the USA, it appears to occur worldwide. The world’s largest cosmetics brand, L’Oréal, reported a revenue decline during the COVID-19 recession, resulting in a 6.71% decrease in overall revenue across all countries. This reflects lower market absorption of their products during times of crisis, which also did not prove any part of the lipstick effect hypothesis.

Although in both the USA and globally, sales may have skyrocketed in the post-recession era, the theory suggesting higher sales during crises remains uncertain in market reality. Statistics have still not been able to empirically prove the lipstick effect from a macroeconomic perspective. One question remains: “How could these people formulate and hypothesize the lipstick effect when, in reality, all cosmetic sales declined during crises?”

A Closer Look: Young Women and the Selective Truth of the Lipstick Effect

So far, we have observed that the lipstick effect hypothesis is not supported by the general sales data of cosmetics during times of crisis. Although several related studies have reported increases and proposed many interesting theories about the effect, statistics do not lie. Instead of showing a general rise, as discussed in the previous sections, the data consistently indicate a decline in cosmetics sales during economic downturns. Therefore, we must return to the most foundational question: How does this theory even exist when statistics show no growth or even a decrease in cosmetics sales?

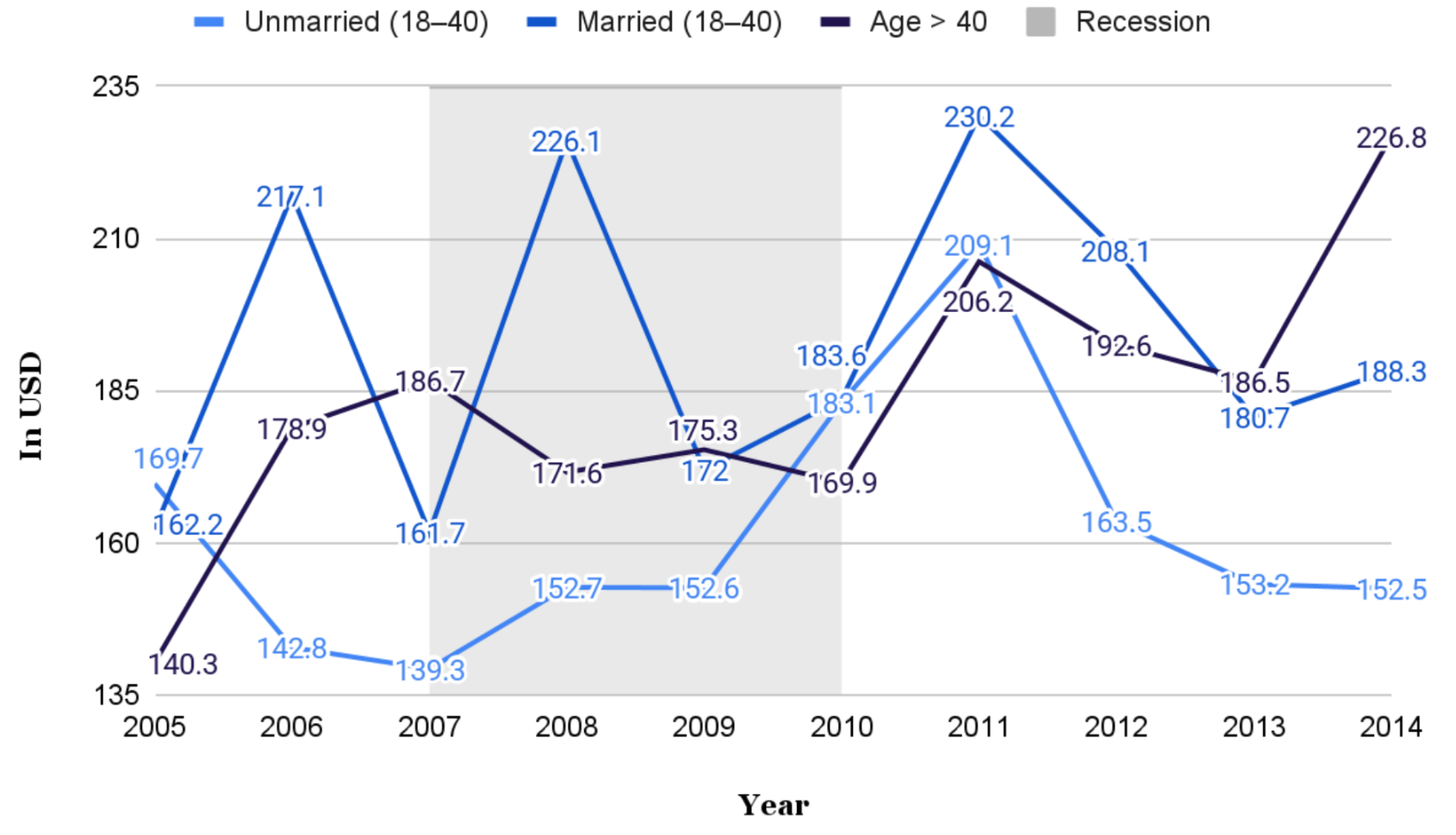

Figure 7. Average Consumer Expenditure by Sub-Group in the USA 2005-2014

Source: Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) Consumer Expenditure Survey Microdata, 2005–2014, cited in MacDonald & Dildar (2020), processed by author.

The phenomenon of the lipstick effect appears to be supported by a comparison conducted by MacDonald and Dildar (2020) on cosmetics expenditures among different subgroups of women (Figure 7). The data show that during times of economic crisis, spending on cosmetics among women aged 18-40 increased by 31.44% for unmarried women and 13.54% for married women, respectively. In contrast, women aged over 40 experienced a decline in cosmetics consumption, with a decrease of 8.98%, from US$186.7 to US$169.9. These findings suggest that the lipstick effect does indeed exist, although its impact is concentrated within specific demographics and does not extend broadly across the entire cosmetics industry or the general economy.

Table 1. Consumer Expenditure Share on Women Aged 18-40 in the USA 2005-2014

Source: Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) Consumer Expenditure Survey Microdata, 2005–2014, cited in MacDonald & Dildar (2020), processed by author.

One of the probable incentives behind this trend is the reallocation of spending from other non-essential goods to cosmetics. Figure 8 shows that during the recession, the expenditure shares for non-primary items such as jewelry, clothing, and watches declined. In contrast, the share allocated to cosmetics increased by 0.013 percentage points. Although this increase is modest, it may indicate a substitution effect, where consumers shift spending away from more expensive luxury items toward more affordable or “frugal” alternatives such as cosmetics during times of economic uncertainty.

This is not only a way for women to treat themselves during economic downturns, but also a means of maintaining control over their own bodies. When people are faced with scarcity, limited choices, social comparison, and environmental uncertainty, they tend to react, cope, and adapt (MacDonald & Dildar, 2020). One way to do this is by gaining a sense of control over their appearance through the use of cosmetics. In times of instability, makeup routines can provide a sense of familiarity, comfort, and structure, helping women to feel more stable in their day-to-day lives (McCabe et al., 2017). It becomes a way of self-identity, reducing stress and vulnerability, and also a form of resistance during hardships (Pussetti, 2023).

While the preliminary factors causing the lipstick effect in cosmetics consumption among young women involve desires for small treats and self-control over their bodies, Bahl et al. (2022) observed that social media culture may also explain part of this phenomenon. Specifically during the recession in 2020, the digitalized world enabled us to have frequent video conferences, exposure to social media, and increased screen time. Prolonged Zoom calls, with close-up shots of our faces, made more and more people begin to focus on their perceived flaws, skewing the perception of their own appearance into self-scrutiny (Bahl et al. 2022).

Moreover, social platforms such as TikTok and Instagram, which have a growing demographic of young women, also set a standard of how ideal beauty is supposed to look (Papageorgiou et al., 2022). This creates an environment full of appearance-based self-comparison and further incentivizes the creation of a social media persona, in contrast to reality (Bahl et al., 2022). Consequently, the high level of cosmetics usage within this age group can be seen as an effort to create a self-image that fulfills digital expectations and serves as an active reaction to social pressures. This combines both internal and external motives that explain the lipstick effect that happens exclusively in cosmetic consumption among young women.

More Personal Than Public: Why the Lipstick Effect Is Not a Macroeconomic Signal

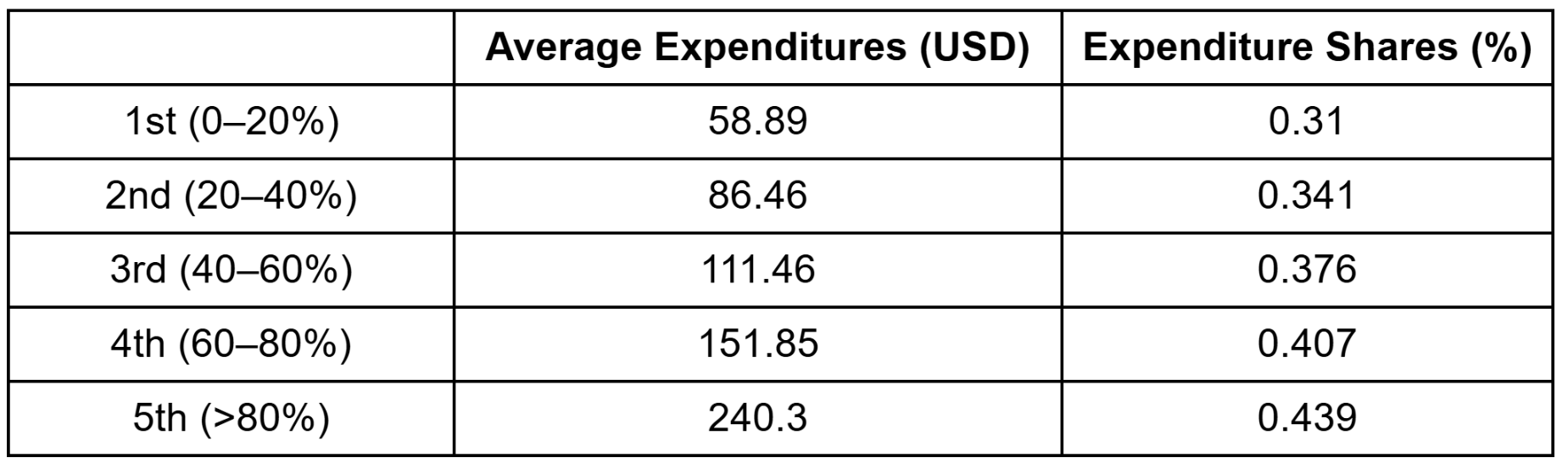

Table 2. Average Annual Cosmetics Expenditures and Expenditure Shares by Income Quintile in the USA 2005-2014

Source: Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) Consumer Expenditure Survey Microdata, 2005–2014, cited in MacDonald & Dildar (2020), processed by author.

Table 2 shows the national average expenditure on cosmetics and clearly demonstrates a positive relationship between income and spending, both in absolute terms and proportionally. It indicates that as income increases, the share of spending on cosmetics also rises. This is evident from the weighted average spending in the first quintile, where households spent only US$58.89, which is just 0.31 percent of their total expenditure. This amount increases significantly across income levels, reaching US$240.30 in the fifth quintile, accounting for 0.439 percent of total spending. Therefore, when income falls, as typically occurs during a recession, spending on cosmetics would be expected to decline. This directly contradicts the lipstick effect as a valid macroeconomic indicator, since an increase in consumption during economic downturns does not align with the expected behavior of normal goods at the aggregate level.

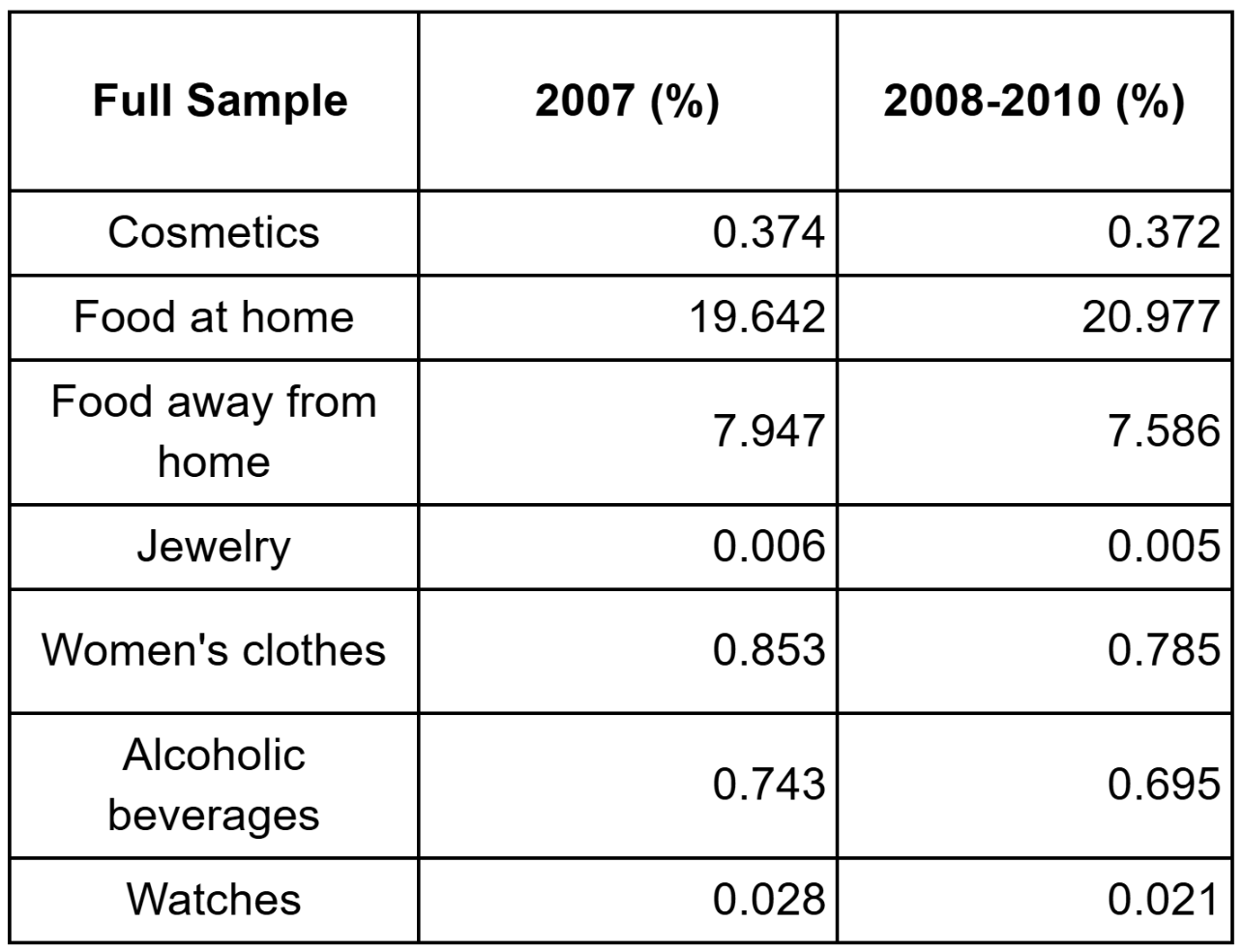

Table 3. Consumer Expenditure Share in the USA 2005-2014

Source: Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) Consumer Expenditure Survey Microdata, 2005–2014, cited in MacDonald & Dildar (2020), processed by author.

Another reason why cosmetics spending does not reflect macroeconomic conditions is simply due to its small share in overall consumer expenditures. The proportion of cosmetics spending is too minimal to substantiate the lipstick effect as a meaningful measure during economic downturns. According to Table 1 and 3, the average share of household spending allocated to cosmetics ranged only between 0.37 and 0.44 percent, which is significantly lower than other categories such as food, which accounts for up to 20 percent of total expenditures, and clothing, which takes around 1 percent. Given these minimal shares, even if cosmetics spending increases slightly during a recession, the change is too marginal to serve as a meaningful substitute purchase during times of financial distress.

End of Word: What Does the Lipstick Effect Really Signal?

The lipstick effect is often cited as an exception during economic crises, suggesting that consumers turn to small luxuries such as cosmetics when finances are tight. But does this idea truly reflect how people behave in difficult times? The data seems to suggest otherwise. In both the 2008 financial crisis and the COVID-19 recession, cosmetics sales declined in the United States and around the world. When cosmetics account for only 0.37 to 0.44 percent of total spending, can any fluctuation in this category really serve as a signal of broader economic behavior? Or have we placed too much weight on a trend that is more hypothetical than empirical? Meanwhile, essential items such as food and clothing continue to show more reliable patterns during downturns, making them stronger reflections of consumer priorities.

Still, perhaps the lipstick effect is not about the economy as a whole, but it is more of an individual response to hardship. Among women aged 18 to 40, cosmetics spending did rise slightly during the Great Recession. What if this was not about luxury, but about maintaining control, expressing identity, or finding comfort? Could this behavior be more about resilience than self-amusement? More about emotional survival than economic signaling? If that is the case, then maybe the lipstick effect is not a macroeconomic pattern at all, but a small window into how people cope in uncertain times. And perhaps the real question is not whether the lipstick effect exists, but what it tells us about the human experience during a crisis.

References

Bahl, A., Garza, H. D. L., Lam, C., & Vashi, N. A. (2021). The lipstick effect during COVID-19 lockdown. Clinics in Dermatology, 40(3). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clindermatol.2021.11.002

Bardey, A., Buentello, D. A., Rogaten, J., Mala, A., & Khadaroo, A. (2023). Exploring the post-COVID lipstick effect: A short report. International Journal of Market Research. https://doi.org/10.1177/14707853231201856

Bitler, M., & Hoynes, H. (2015). Heterogeneity in the Impact of Economic Cycles and the Great Recession: Effects within and across the Income Distribution. American Economic Review, 105(5), 154–160. https://doi.org/10.1257/aer.p20151055

Daniil, M., Snezhana, M., Elena, R., & Valeria, K. (2020). Sustainable growth in times of crisis: L’Oréal Russia. Emerald Emerging Markets Case Studies, 10(4), 1–20. https://doi.org/10.1108/eemcs-06-2020-0219

EJARQUE, J. M. (2008). Uncertainty, Irreversibility, Durable Consumption and the Great Depression. Economica, 76(303), 574–587. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-0335.2008.00694.x

Etcoff, N. L., Stock, S., Haley, L. E., Vickery, S. A., & House, D. M. (2011). Cosmetics as a feature of the extended human phenotype: modulation of the perception of biologically important facial signals. PloS One, 6(10), e25656. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0025656

Frasquilho, D., Matos, M. G., Salonna, F., Guerreiro, D., Storti, C. C., Gaspar, T., & Caldas-de-Almeida, J. M. (2016). Mental health outcomes in times of economic recession: a systematic literature review. BMC Public Health, 16(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-016-2720-y

Geroski, P., & Gregg, P. (1993). Coping the Recession. National Institute Economic Review, 146(1), 64–75. https://doi.org/10.1177/002795019314600105

Griskevicius, V., Ackerman, J. M., Cantú, S. M., Delton, A. W., Robertson, T. E., Simpson, J. A., Thompson, M. E., & Tybur, J. M. (2013). When the Economy Falters, Do People Spend or Save? Responses to Resource Scarcity Depend on Childhood Environments. Psychological Science, 24(2), 197–205. https://doi.org/10.1177/0956797612451471

Hill, S. E., Rodeheffer, C. D., Griskevicius, V., Durante, K., & Andrew Edward White. (2012). Boosting beauty in an economic decline: Mating, spending, and the lipstick effect. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 103(2), 275–291. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0028657

Li, W., Zhen, C., & Dorfman, J. H. (2019). Modelling with flexibility through the business cycle: using a panel smooth transition model to test for the lipstick effect. Applied Economics, 52(25), 2694–2704. https://doi.org/10.1080/00036846.2019.1693701

L’Oreal. (2025, March 24). L’Oréal financial performance in 2024: sales, profit, dividends… | L’Oréal Finance. L’Oréal Finance. https://www.loreal-finance.com/en/annual-report-2024/financial-performance/

MacDonald, D., & Dildar, Y. (2020). Social and psychological determinants of consumption: Evidence for the lipstick effect during the Great Recession. Journal of Behavioral and Experimental Economics, 86(101527), 101527. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socec.2020.101527

McCabe, M., de Waal Malefyt, T., & Fabri, A. (2017). Women, makeup, and authenticity: Negotiating embodiment and discourses of beauty. Journal of Consumer Culture, 20(4), 656–677. https://doi.org/10.1177/1469540517736558

Netchaeva, E., & Rees, M. (2016). Strategically Stunning: The Professional Motivations Behind the Lipstick Effect. Psychological Science 2016, 27(8), 1157–1168. https://doi.org/10.1177/0956797616654677

Papageorgiou, A., Fisher, C., & Cross, D. (2022). “Why Don’t I Look like her?” How Adolescent Girls View Social Media and Its Connection to Body Image. BMC Women’s Health, 22(1), 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12905-022-01845-4

Pussetti, C. (2023). Life comes first, but lifestyle also matters: aesthetic responses to pandemic angst. Análise Social, 58(1 (246)), 172–191. https://www.jstor.org/stable/27204659

Raza, M., Khalid, R., Maria, S., & Han, H. (2024). Luxury brand at the cusp of lipstick effects: Turning brand selfies into luxury brand curruncy to thrive via richcession. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 79, 103850–103850. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jretconser.2024.103850

Schaefer, K. (2008, May 1). Hard Times, but Your Lips Look Great. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2008/05/01/fashion/01SKIN.html?pagewanted=all

Statista. (2025, February 28). Revenue of the cosmetics market in the United States from 2019 to 2030. Statista.com. https://www-statista-com.ezproxy.ugm.ac.id/forecasts/1272319/united-states-revenue-cosmetics-market