Author: Nawfal Aulia Luthfurrahman

Indonesian cuisine has colorful flavors as a symbol of national wealth and is marked by sugar as a symbol of life. The philosophy of this cuisine comes from the rich spices produced by Indonesia in various regions supported by its culture of taste seekers. However, one prominent identity of Indonesian cuisine, especially Javanese cuisine, is its sweetness and the use of sugar cane as the main ingredient.

The importance of sugar to the Javanese people can be traced to their culture, where sugar makes its mark in the form of a song called “dhandhanggula,” a symbol of morality and spirituality. In more practical proof, Javanese cuisine such as apem, cucur, jadah, jenang, and more consist of sugar as one main ingredient of the product. This evidence shows that sugar is a crucial part of Javanese people’s daily consumption by culture and a social approach.

Eventually, the sugar consumption tradition led to several implications for the Indonesian economy and foreign exchange. Indonesia was obliged to import 3.36 million tons of sugar, the biggest in the world, and cost national foreign exchange worth $2.4 billion in 2023. However, the question arises as Indonesia’s agricultural power in its plantation and weather conditions are well suited for sugar cane industries, so how did Indonesia’s sugar industry flop and not achieve its highest stakes? Once Indonesia’s sugar industry was dominant, we will discuss the process and history behind that.

The Chronological History of the Dutch Indies’ Sugar Industry

The development of the modern sugar industry in the Dutch East Indies began when the Netherlands returned to power after experiencing various prolonged wars. The Netherlands at that time was in the process of reconstruction after experiencing the Napoleonic War and the war against Belgium. The Dutch government was also still in debt to VOC shareholders after its collapse due to massive corruption. In such a distressed state, the Dutch government was forced to implement a policy of mercantilism to restore its economy.

The mercantilist system implemented by the Dutch government focused on protecting national needs independently, as well as maximizing their resources for the national interest. The Netherlands tried to reduce the amount of imports by exploiting its colonies from the early to mid-19th century. The Netherlands also forced its colonies to produce valuable export commodities according to the needs of its homeland without considering the welfare of its colonies. The Dutch East Indies became the actor most affected by Dutch economic policy, especially after the appointment of Van Den Bosch as Governor-General.

Dutch influence at the time strengthened after the appointment of Van Den Bosch as Governor-General of the Dutch East Indies (1830-34). Van Den Bosch introduced a cultivation system that required the communities and villages of Java’s North Coast to set aside land to farm export commodities, especially coffee, indigo, and sugar cane. The Dutch also implemented a burdensome land tax system on Javanese landowners to ensure the cultivation system worked (Ricklefs, 2008).

Throughout the implementation of the cultivation system policy, Javanese people were forced to deposit the harvest of their export commodities in exchange for a fixed rate determined by the Dutch government. Farmers were also forced to achieve specific harvest targets, or they would be charged land taxes that had to be paid by the Dutch government. Meanwhile, the compensation provided by the Dutch government, Cultuurrpoceten, needed to be fairer because it used a fixed rate rather than following the high world market prices at that time.

The proceeds from sugar production at that time were then shipped to the Netherlands using ships owned by the Dutch company, Netherlandsche Handel-Maatschappij, and sold using auctions by semi-private companies in which the king was a significant shareholder in order to benefit the home country. This mercantile policy gave the Netherlands enormous profits during the period 1832-52, with colony revenues reaching 19% of total Dutch revenues (Fasseur, 1992). These profits placed the Netherlands as the dominant player in the trade of tropical products, paid off the VOC’s debts, and also built the national railway (Widodo, 2006).

The cultivation system was run by the Dutch government until 1860, just as the liberal party rose in the national political constellation. The liberal party, as the leader of the liberalism movement, advocated for the establishment of free enterprises and the reduction of government intervention in economic matters, especially in colonized countries, including the Dutch East Indies. Through this liberalism movement, the Dutch government began to open up avenues for private enterprise in the colony’s economy (Ricklef, 1991).

Dutch economic liberalism also forced it to abandon its monopoly on tropical products such as tobacco, coffee, tea, and sugar in the national economy. The group also demanded a guarantee of free trade that would allow them to sell, buy, or open tropical merchandise from the colony without government interference. An agrarian law was also passed by the Dutch government in 1870, which allowed foreign private investors to lease land for 75 years as well as build private industries in the Dutch East Indies (Widodo, 2006).

The hegemony of liberal parties in the Dutch East Indies ended when they suffered a major defeat in the Dutch general election of 1901. One of the major proponents of the ethical policy was Abraham Kuyper, the leader of the neo-Calvinist Anti-Revolutionary Party. Kuyper criticized the liberal government’s exploitative policies in the Dutch East Indies and advocated a moral obligation to improve the welfare of the indigenous population through education, economic development, and greater autonomy. His views significantly influenced the adoption of the ethical policy after his party’s electoral success in 1901 (Ricklefs, 2008; Vickers, 2005; Kribb, 2004 ).

During this period, it was the conservative and religious-based parties that supported the ethical policy movement towards the colony, such as van Deventer and Douwes Dekker (Multatuli). This policy was then implemented in the form of improved agrarian systems, open educational opportunities, and transmigration programs. However, by the late 1920s, the Dutch East Indies government began to abandon this ethical policy as a reaction to the increasing demand for independence from the local Indonesian communities (Boogaard, 2013; Koch, 1950).

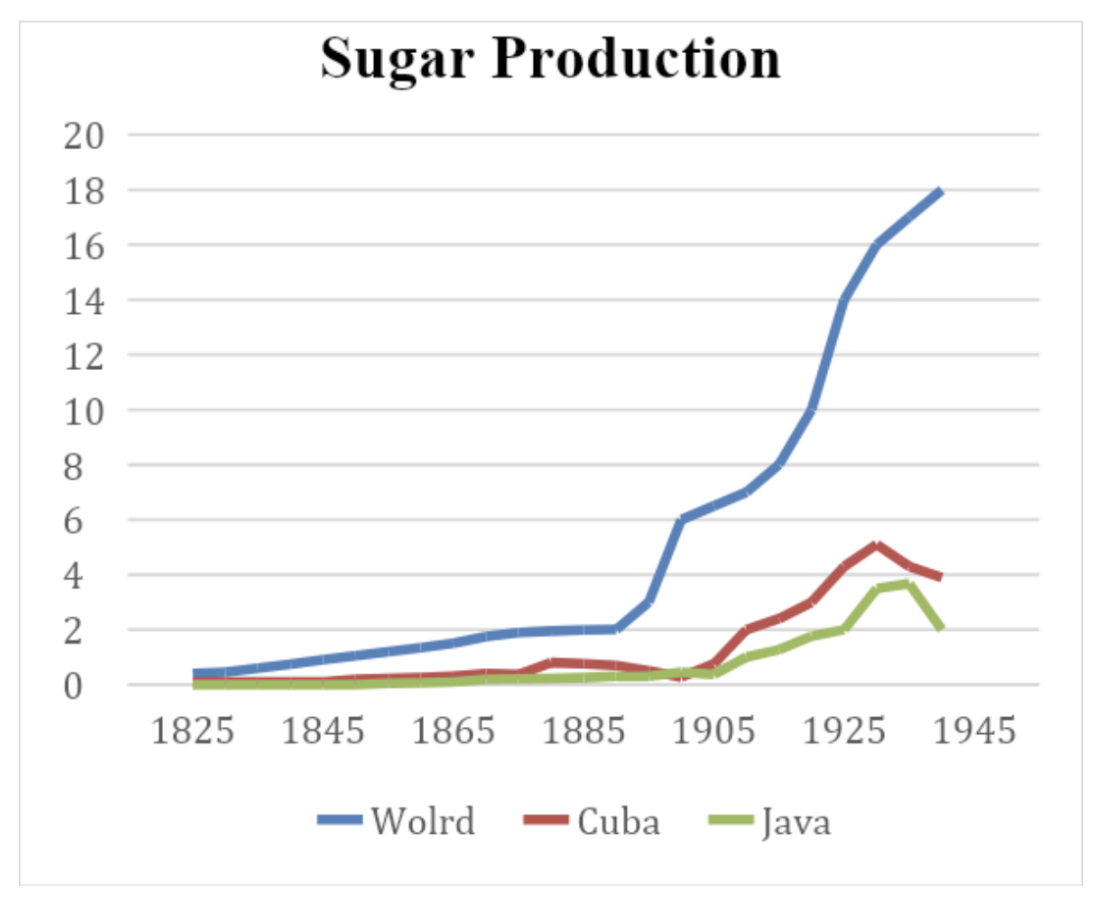

After 1920, the sugar industry in the Dutch East Indies began to decline after the invention of the mass-produced automobile in the early 20th century, which reduced the incentive for financiers to invest money in the sugar industry in the Dutch East Indies. This was exacerbated by developments in the agrarian field, which caused the sugar cane plant to no longer be exclusive to the Dutch East Indies. This was evidenced by the increase in sugar supply in the world despite the decline in production in the Dutch East Indies at the beginning of the 20th century.

World War 1 was also an essential factor in the shift in the supply of the sugar industry and plantations. In the revitalisation period, many countries in Europe and North America switched to using more efficient and cheaper petroleum-based industrial machinery. The shift in demand caused colonies such as South America, the Middle East, and the Dutch East Indies to become new areas for exploration and extraction of petroleum resources (Rubio-Varas, 2019). As a result, the focus of the Dutch government shifted to the extraction of natural resources such as cobalt, rubber, copra, petroleum gas, and palm oil rather than the declining sugar industry (Widodo, 2006).

The Economic Analysis of Dutch Indies’ Sugar Industry

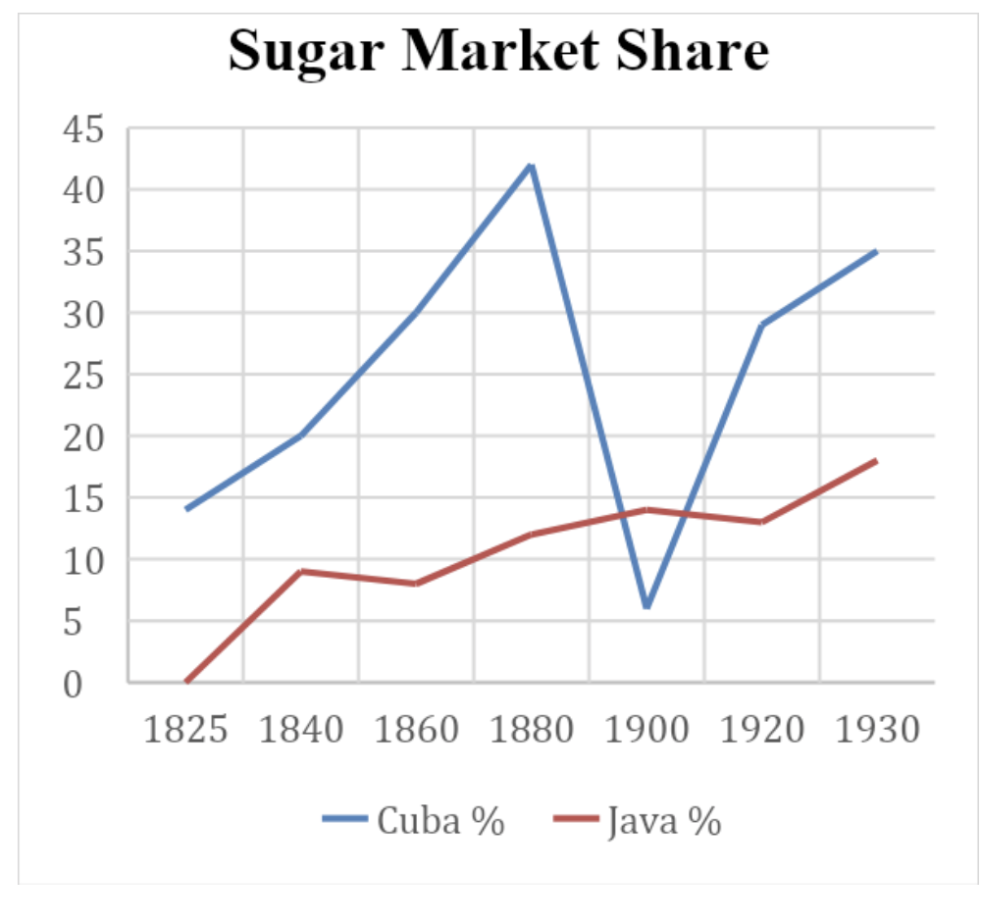

The Dutch East Indies was once World’s second-largest sugar producer from 1840 until its peak in 1930. During this time, the Dutch East Indies only lost to the South American region of Cuba, which controlled 35% of the world’s sugar market share in 1930. Meanwhile, the Dutch East Indies held 19% of the share of world sugar cane, with a total sugar production of 2 million tons in the same year. The economic value generated from the sugar cane industry in the Dutch Indies reached 4% of Dutch GDP and a third of Netherlands revenue at its peak (Curry-Machado,2012).

Aside from its impact on values, the Dutch East Indies sugar business employed up to 25% of the native Javanese people; the precise number of workers employed was around 2.5 million, excluding free labor. Along with establishing 70,000 sugar growers who produced cane for 59 plants, the Dutch eventually expanded to include 94 factories and a sizable portion of the Javanese populace (Elson, 1994). As this sector grew, 320,00-1,400,000 Javanese households were eventually compelled to oversee the sugar industry through farming systems (Curry-Machado, 2012).

Even though the effects of economic growth caused by the sugar industry have been around for decades, Olken (2017) explains that the economic spoils to the Indonesian sugar industry can still be felt across the broad spectrum of modern Java. He explained that this regional agglomeration phenomenon occurred in subjugated villages several kilometers from colonial sugar factories, whether they were still operating. Olken statistically describes the effects of agglomeration in several sectors, such as education, land ownership, and the economic structure of society.

People living close to industry tend to have lower participation in the agricultural sector, with 20 to 25 percent of individuals choosing to work in other industrial sectors. On the other hand, areas adjacent to historical factories saw an increase of around seven percent in the number of individuals working in the manufacturing sector. Based on these two facts, Olken (2017) assumes that the historical effect of industry built during the colonial period is a crucial factor in the industrialization of local society. However, it is not the only factor in society’s industrialization, considering that industrialization also occurs as a response to global demand.

In addition to the noted impact, regions within several kilometers of the colonial sugar industry exhibit an employment rate approximately 10 percent higher than areas over 20 kilometers away from these industrial centers. This surge in employment has coincided with the transformation of nearby regions into vibrant urban hubs. Formerly designated as industrial zones, these areas have experienced a significant uptick in population density, particularly in locales such as Pekalongan, Semarang, Kudus, and Surakarta.

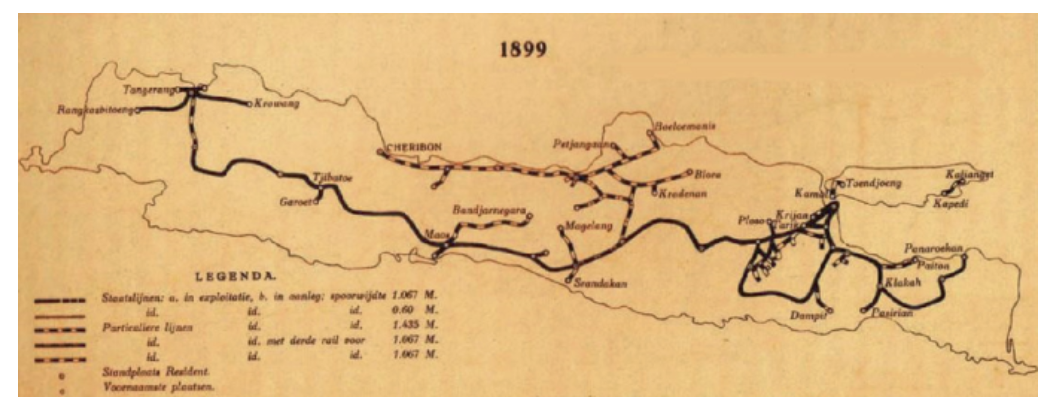

Economic growth around colonial sugar factories was also followed by other supporting infrastructures such as railroads and ports. As seen in the railway map above, railway development in the Dutch East Indies focused on the sugar industry and nearby port cities, such as Cirebon, Semarang, Kudus, Surabaya, and Malang.. Olken (2017), in his research, compared areas within 0-1 km of sugar factories to have a railroad density more than twice as large as the sample mean compared to areas within 5-10 km of Dutch sugar factories.

Beside infrastructures development, the fact that villages were very close to the Dutch East Indies factories had an enormous effect on educational provision and outcomes. Empirical evidence suggests that regions adjacent to factories saw a higher number of high schools by 2 percent in 1980, while the people living close to a factory tended to have higher years of schooling as compared to those who lived farther from a factory. This pattern was however constant across different groups, showing a long-lasting impact on educational levels. Also, the percentage of high school and primary completion was higher in the areas around factories, with younger cohorts particularly affected. These assertions suggest the lasting effect of industrial presence on educational possibilities and successes for this area (Olken, 2017).

These areas were originally Dutch-owned plantations and industries, which were transformed into population centers after independence. These cities developed because of massive economic and trade activities during the Dutch colonial period. As a result, much of the economic development is still centralized in these areas, from the development of society, politics, to the number of people involved in the manufacturing industry (Amalia, 2018).

Path Dependency

The history of the sugar industry in Indonesia reveals how path dependency works, linking the past events and decisions to the future relations whereby a certain path is followed by the others leading to a self-reinforcing phenomenon (Mahoney, 2000; Pierson, 2000). In such colonial context, sugar factories build upon regional agglomerations and create a basis for industrialization and urbanization in Java.

According to Olken (2017), sugar factories in the colonial time were the reason for the long term economic impacts, population density, and educational attainment of its surrounding areas. The fact that this development process is cumulative can be ascertained by the higher employment rates, greater growth of manufacturing sectors and better education outcomes found in regions which are closer to historical sugar factories.Along with this, the growth of supporting infrastructure like railways, ports and built-up areas near the industrial hubs also boosted the expanding of cities and trade activities. Transportation and other infrastructural legacies reinforced this economic growth and development which in turn created a virtuous cycle, consolidating the development process (Redding & Turner, 2015).

According to the concept of path dependence theory, the patterns and effects derived in the colonial era that happened during the times of sugar plantations are the sources of Indonesia’s society today (Mahoney 2000; Pierson 2000). This approach, having been formed in the past, is crucial to realize the current understanding of economic dynamics and the policies most suitable to ensure the country’s stability at the moment. The landing of the sugar factories and the associated infrastructure development activities of the Dutch colonial time led to some regional agglomeration trends which continue to have an impact on Indonesia’s socio economic landscape (Olken, 2017).

Those neighborhoods that are located close to the old sugar factories show the highest levels of industrialization, urbanization, and education, thus implying that even today the influence of these historical events can be felt (Redding & Turner, 2015). Besides that, the state-contingent feature can result in lock-in situations in which already consolidated patterns become shielded from modifications and hence might prevent even distribution of development (Mahoney, 2000). Such path dependents must be taken into account for formulating policies that are specific to context, capable of overcoming institutional inertia, and which produce sustainable and resilient development pathways (Acemoglu et al., 2001; Pierson, 2000).

Conclusion

In the end, the Indonesian sugar industry is an influential feature of the history of economic prosperity; it is in the Javanese island, where it caused the development of prosperous cities around the sugar factories. Nonetheless, this process of industrial expansion triggered the adoption of some infrastructures such as railroads and ports which then further contributed to the regional concentration of development in sugar-producing areas. The proximity of school to factories became a critical factor for the education of the locals, many of whom benefited from the increased educational opportunities and attainment which the era of industrialization created and lives on to this day. Showing these forces from an angle of a path-dependent analysis reveals both widened legacies of postcolonial industrialization and their present state which define and limit the social and economic future of Indonesia. The historical course of sugar manufacturing in Indonesia is a non-simpler process which does not consist of a linear phase but a series chapter related to historical circumstances that have befallen the country and the impacts they had on the nation’s economic developments.

REFERENCE

Acemoglu, D., Johnson, S., & Robinson, J. A. (2001). The colonial origins of comparative

development: An empirical investigation. American Economic Review, 91(5), 1369-1401.

https://doi.org/10.1257/aer.91.5.1369

Atkinson, C. L. (2014). Deforestation and Transboundary Haze in Indonesia. Environment and

Urbanization ASIA, 5(2), 253–267. DOI: 10.1177/0975425315577905

Curry-Machado, J., & Bosma, U. (2012). Two Islands, One Commodity: Cuba, Java, and the Global

Sugar Trade (1790-1930). New West Indian Guide / Nieuwe West-Indische Gids, 86(3-4),

237-262. DOI: 10.1163/13822373-90002415

Dagm Alemayehu Tegegn, & Dhont, F. (2023). The downhill journey of the Java sugar economy in the

Netherlands Indies (Later Indonesia) from the late 19th century to the mid-20th century. Cogent

Arts & Humanities, 10(1). DOI: 10.1080/23311983.2023.2220213

Dell, M., & Olken, B. (2017). The Development Effects of the Extractive Colonial Economy: The

Dutch Cultivation System in Java. DOI: 10.3386/w24009

Fathimah, F. A. (2018). The Extractive Institutions as Legacy of Dutch Colonialism in Indonesia A

Historical Case Study Fida Amalia Fathimah Master Programme in Industrial Management and

Innovation Masterprogram i industriell ledning och innovation.

http://www.diva-portal.org/smash/get/diva2:1285721/FULLTEXT01.pdf

Greener, I. (2019, January 9). Path dependence. Encyclopedia Britannica.

https://www.britannica.com/topic/path-dependence

Knight, G. R. (1980). From Plantation to Padi-field: The Origins of the Nineteenth Century

Transformation of Java’s Sugar Industry. Modern Asian Studies, 14(2), 177–204. DOI:

10.1017/S0026749X00007307

M.d.Mar Rubio-Varas. (2019). The First World War and the Latin American transition from coal to

petroleum. Environmental Innovation and Societal Transitions. Volume 32. Pages 45-54. ISSN

2210-4224. DOI: 10.1016/j.eist.2018.03.002

Mahoney, J. (2000). Path dependence in historical sociology. Theory and Society, 29(4), 507-548.

https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1007113830879

Pierson, P. (2000). Increasing returns, path dependence, and the study of politics. American Political

Science Review, 94(2), 251-267. https://doi.org/10.2307/2586011

Redding, S. J., & Turner, M. A. (2015). Transportation costs and the spatial organization of economic

activity. In Handbook of Regional and Urban Economics (Vol. 5, pp. 1339-1398). Elsevier.

https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-444-59531-7.00020-X

Trouvé, H., Couturier, Y., Etheridge, F., Saint-Jean, O., & Somme, D. (2010). The path dependency

theory: analytical framework to study institutional integration. The case of France. International

Journal of integrated care, 10, e049. DOI: 10.5334/ijic.544

White, N. J. (2017). The Settlement of Decolonization and Post-Colonial Economic Development:

Indonesia, Malaysia, and Singapore Compared. Bijdragen tot de taal-, land- en volkenkunde /

Journal of the Humanities and Social Sciences of Southeast Asia, 173(2-3), 208-241. DOI:

10.1163/22134379-17302003

Widodo, T. (2006). FROM DUTCH MERCANTILISM TO LIBERALISM: INDONESIAN

HISTORICAL PERSPECTIVE. Journal of Indonesian Economy and Business (JIEB), 21(4),

323–343. https://jurnal.ugm.ac.id/jieb/article/view/39915/22488

Yusuf Perdana and Henry, Susanto and Ekwandari, Yustina Sri (2019) Dinamika Industri Gula Sejak

Cultuurstelsel Hingga Krisis Malaise Tahun 1830 – 1929. HISTORIA: Jurnal Program Studi

Pendidikan Sejarah, 7 (2), 227-242. ISSN 2337-4713