Author : Aulia Davetta Athif

Introduction

The 21st century is plagued with a looming climate crisis and rising inequality, the pandemic also stalled the progress against poverty. We often see these problems as separated and detached from each other. However, these problems are often interrelated and influence one another – climate change can exacerbate poverty and inequality, and vice versa. In this article, we will explore some of the relationships between climate change, poverty, and inequality.

Current state of affairs

For the past few years, there have been many events that are attributed to climate change. From heat waves that are currently affecting Pakistan and India where surface temperature reached 50°C (WMO, 2022) and Western North America in 2021 where it reached around 49°C (Reuters, 2021) to a new record of CO2 concentration in the atmosphere, where in May 2022 it reached a new high of 422 ppm, beating the previous record of 419 ppm recorded in May 2021. Atmospheric methane concentrations have also recorded a historic increase of 17 ppb, up from 15.3 ppb in 2020. (NOAA, 2022). It is especially dangerous as methane is >25 times more potent in trapping heat than CO2 (EPA, 2021). Meanwhile, investigative reporting from the Guardian shows that oil and gas companies are still planning to invest more in so-called ‘carbon bombs’, these projects combined could release up to 646 gigatonnes of CO2 emissions, overshooting the carbon budget of 500 GtCO2 that were set by the IPCC to have a 50% chance of limiting warming below 1.5°C.

On the other hand, gains in reducing global poverty and inequality have stalled as a result of the Covid-19 pandemic. In many countries, income growth for the bottom 40% saw a decline that is greater than national averages (UN, 2022). The average Gini Index of emerging and developing countries is estimated to increase by 6%, reversing the gains made since the global financial crisis in 2007 (UN, 2021). Generally, income inequality has increased not only in developing countries, but also in developed countries such as the US (UN, 2020). From 2001 to 2016, the median net worth of upper-income families in the US increased by 33% while middle-income families experienced a decrease of 20% and 45% for low-income families. Furthermore, only the top 20% of households gained wealth since the Great Recession in 2007, exacerbating inequality to a point where the richest 5% of families owned 248 times more wealth than the lowest 20% (Pew Research Center, 2020).

Figure 1. Median family wealth and aggregate family wealth in the US, by income tier (Pew Research Center, 2020)

Unequal impact: Emitted the least, affected the most

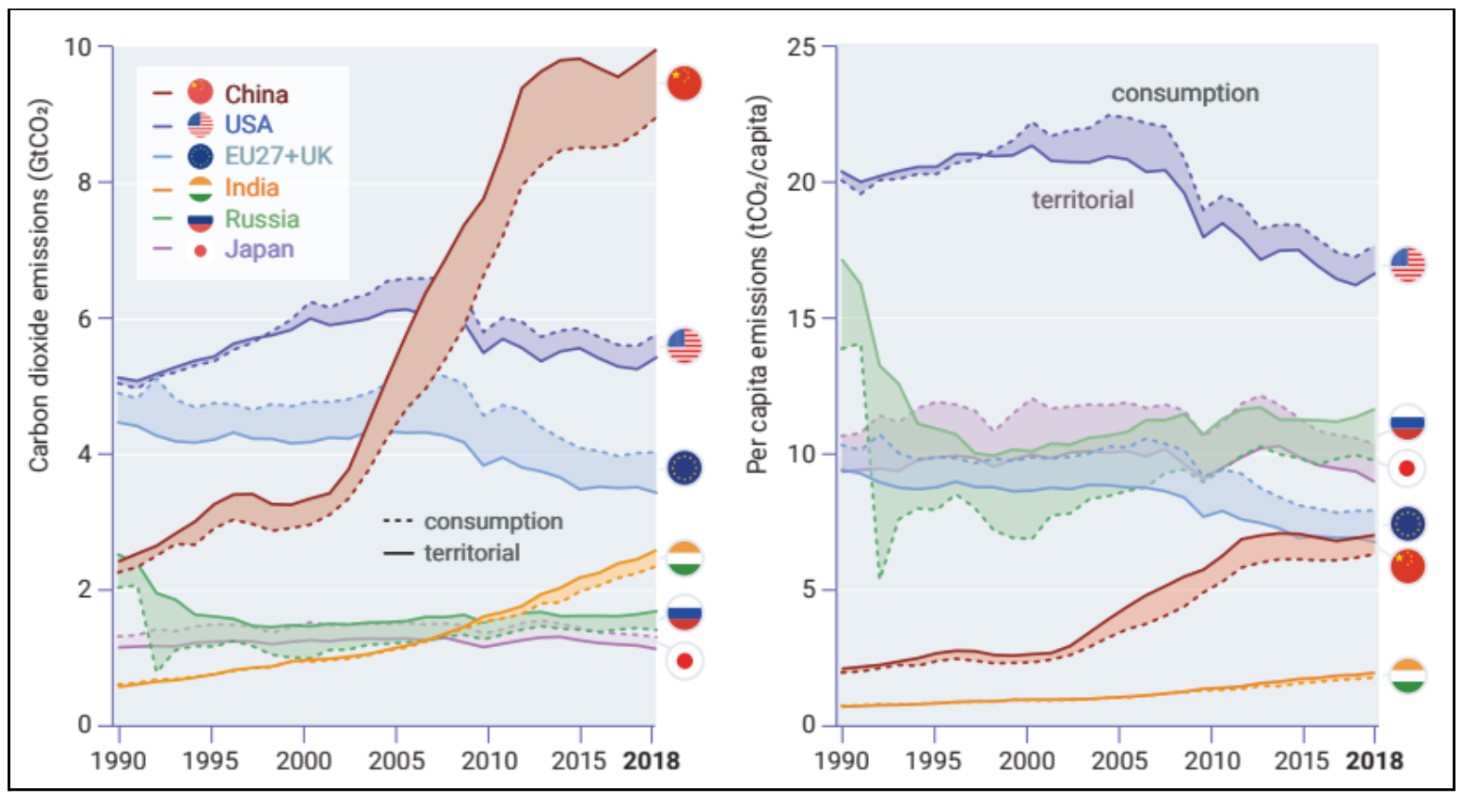

Climate change, by its own nature, is a very global issue that is affecting virtually all countries. However, the progression and severity of those impacts are deeply unequal and lean heavily on developing countries that have historically emitted less carbon than developed countries. Currently, the seven biggest carbon emitters are China, the US, the EU, India, Russia, and international transport, accounting for 65 percent of global emissions (UNEP, 2020).

Figure 2. Consumption-based and territorial-based CO2 emissions for the top 6 emitters (UNEP, 2020)

Based on Figure 2, there is a pattern where the emissions of emerging countries are increasing while for developed countries it is stagnating. A second pattern can be noticed where in emerging countries, territorial-based emissions are larger than consumption-based emissions while in developed countries it is the reverse. This is because developed countries such as the US and EU are importing goods from emerging countries such as China or India for consumption. In short, some of the reduction in emissions is not actually reduced, but ‘exported’ to emerging countries.

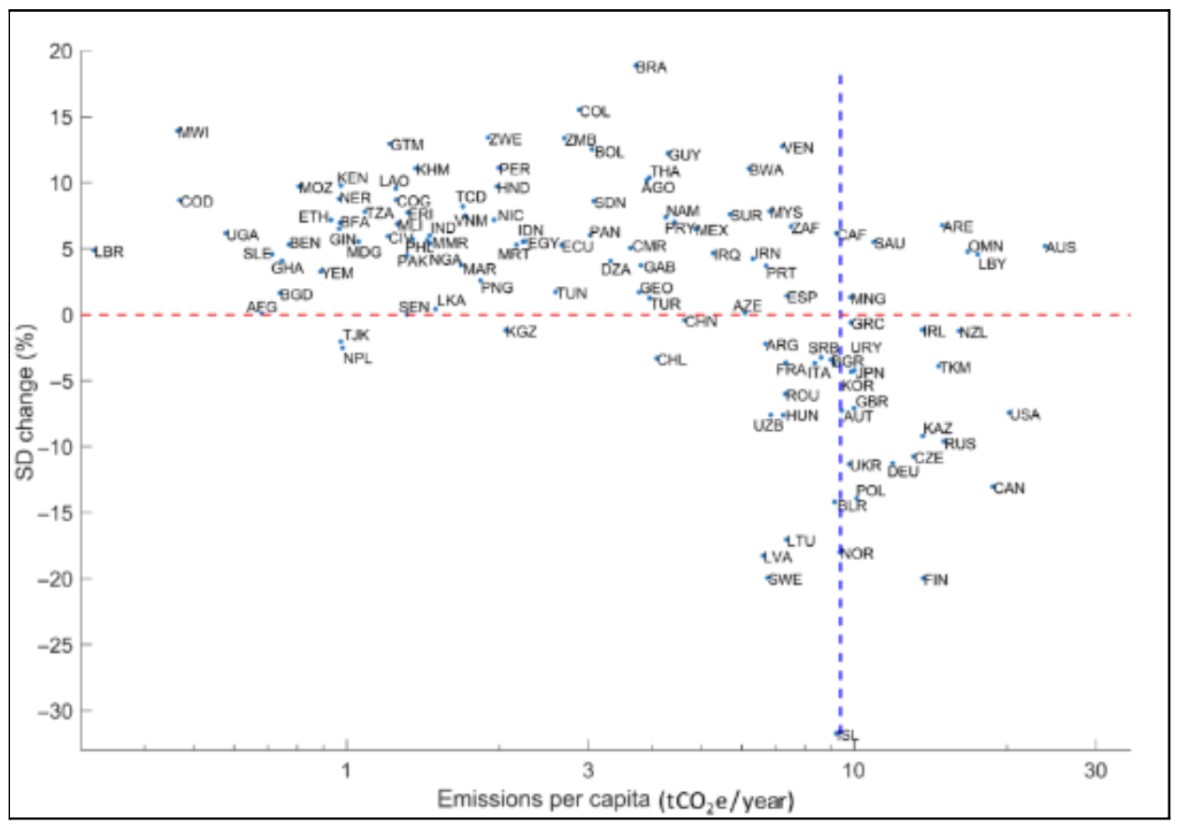

Countries that emitted less are disproportionately impacted as those countries are located at hotspot regions of increasing temperature variability that are going to expose them to greater weather and climate shocks. Temperature fluctuations are projected to decrease in countries with high per capita GDP and increase in countries with low per capita GDP, resulting in a more stable temperature for developed countries in mid to high-latitudes but more fluctuate in low-latitude regions in where the majority of developing countries are located. This will cause a dual challenge of poverty and increasing climate instability in developing countries (Bathiany et al., 2018)

Figure 3. Change in temperature variability and greenhouse gas emissions per country (Bathiany et al., 2018)

Furthermore, the impact of climate change on economic growth is larger for countries in the Tropics and the Southern Hemisphere. Countries that currently have lower per capita incomes are projected to experience a larger negative growth than those with higher per capita income. This would result when temperature rises by 1.5°C or higher, there would be a divergence in growth where low-income countries are regressing faster than high-income countries. Overall, a 1.5°C increase in temperature would reduce the average GDP per capita by 8% and 13% at 2°C. (Pretis et al., 2018)

Figure 4. Projected impact of climate change on annual GDP per capita growth (Pretis et al., 2018)

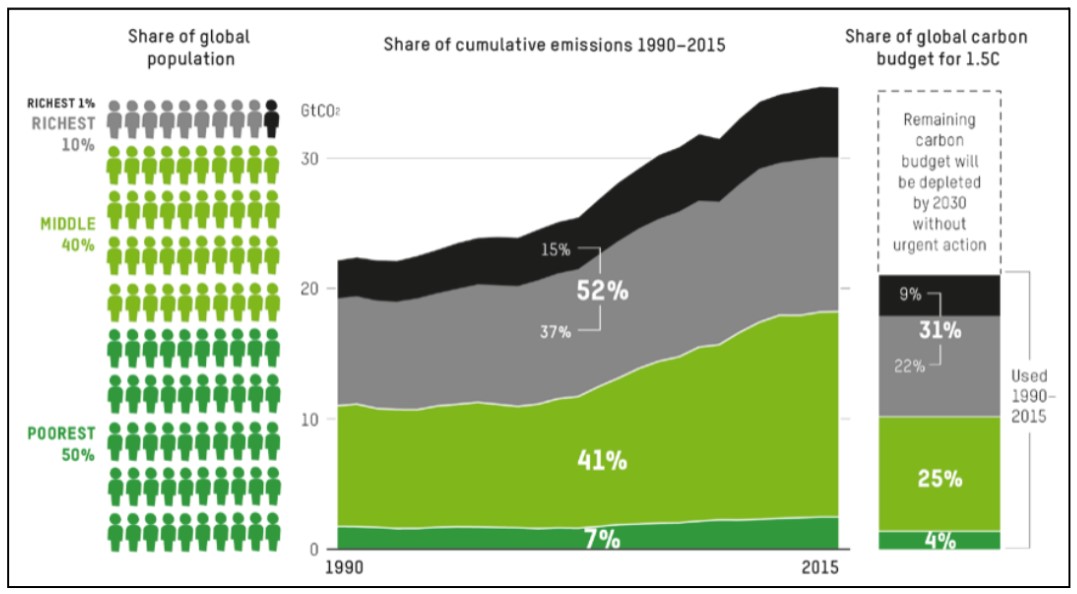

The inequities of climate change can also be seen in another perspective, one that is not based on countries, but on levels of wealth. From 1990 until 2015, carbon emissions grew by 60% and the richest 10% of humanity contributed 52% to that growth, far larger than the poorest 50% that only contributed 7%. The average individual in the top 10% emitted on average 25.3 tonnes of CO2 in 2015, while individuals in the bottom 50% on average emitted 0.69 tonnes of CO2 (Oxfam & SEI, 2020). Moreover, inequality in emissions is more related to economic factors rather than geographical as economic drivers are the main influencer of consumption-based CO2 emissions, meaning that the richer the population, the higher the consumption, and higher consumption means higher emissions (Teixidó-Figueras et al., 2016).

Figure 5. Share of cumulative emissions from 1990 to 2015 based on income groups (Oxfam & SEI, 2020)

Unequal resilience: Earned the least, suffered the most

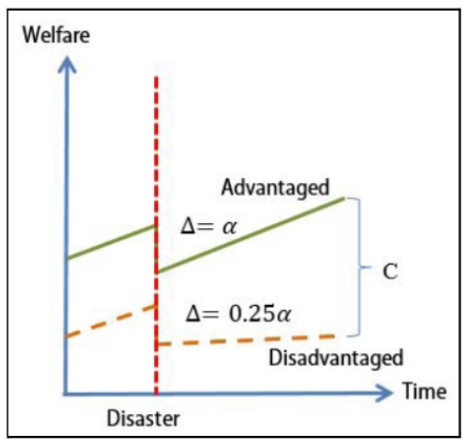

Low-income groups and people in poverty represent a small percentage of carbon emissions, but these groups would face the brunt of climate change. Research from Islam et al. (2017) shows that low-income groups lacks the ability to cope and recover quickly from disasters as they have low resillience attributed to their lack of resources necessary to adapt and rebuild. One example of this is when hit by disasters, low-income groups face the dilemma of preserving human or physical capital as they do not have the resources to preserve both, in the end they have to sacrifice their physical capital to preserve themselves, rendering them poorer. Another important point is that low-income groups tend to not have insurance, making them more susceptible to high losses especially agricultural losses, because of this they tend to remain with low risk but low yield crops, forgoing higher potential earnings (Clarke et al., 2015).

Figure 6. Difference trajectories between advantaged and disadvantaged groups following a disaster (Islam et al., 2017)

More often than not, low-income groups live in areas that are risky and more exposed to natural hazards. Poor people are disproportionately living in areas that are going to be more prone to droughts and floods as a result of climate change, poorer urban neighbourhoods are located in areas with high risk of flooding, as those areas have lower prices and low-risk areas are beyond their financial capabilities (Winsemius et al., 2018). The relationship runs in both directions, poor people live in risky areas because it is cheap and affordable to them, but living in those areas makes them more susceptible to climate hazards that can impact their assets and livelihoods. Combined with low resilience, poor people will experience more climate-related disasters in the future and will lose more from those disasters than people with higher income (Hallegatte et al., 2018)

In addition, increase in temperature and its variability would impact agricultural productivity and ultimately food prices. Increased temperatures and frequent disasters also enhances the transmission of diseases. Both of these channels are one of the main ways of climate change on increasing poverty (Hallegatte et al., 2017)

Figure 7. Number of additional people in extreme poverty by 2030 based on four different scenarios (Hallegatte et al., 2017)

Move or endure: a dilemma of the poor living in climate hotspots

Water stresses and extreme drought as an effect of climate change contribute towards the voluntary and involuntary migration of people. Changing rainfall patterns and extreme temperature variability reduces agricultural production and reduces the income of people that are dependent on it. This prompted people to move from climate hotspots to a more climate-stable area – such is the case for farmers migrating from Mexico to the US (Wrathall et al., 2018). Recent climate-induced migration trends show that there is a net out-migration from drylands and mountainous regions and a net in-migration towards urban coastal zones. It is a result of increasing temperatures and water scarcity that contribute to lower crop yields that influence people to migrate into urban areas, although it doesn’t mean coastal areas do not suffer from the impacts of climate change (Adger et al., 2018).

On average, 24 million people are displaced per year from weather-related disasters over the past decade – in the first half of 2020 there are 9.8 million people that were displaced by disasters such as by wildfires, extreme storms, and droughts. In 2030 it is predicted that 140 million people could be displaced from climate change impacts. These migrants face many insecurities in their destination such as social exclusion and poor living conditions – often living in urban areas that are prone to flooding and landslides (Adger et al., 2020). Migration to coastal urban areas poses a risk to migrants, they commonly face discrimination and seclusion from the local populace and vunerable to poverty as they left many of their physical capital (Adger et al., 2018). Therefore, migration to find better livelihoods can lead to worse outcomes and lead them deeper into poverty.

It is why some people in climate hotspots are not willing to migrate. Research by Adams (2016) that interviewed people living in the Peruvian Andes shows that although 77% of them agreed that there is a negative change in the local climate, they are unwilling to move as they think their situation would not change for the better. Although, some that have the intention to migrate cannot do it from lack of resources necessary to migrate, from lack of money or place to live in their destination. These people are described as ‘trapped’, where the impact of climate change is reducing their incomes and they are unable to move and find better livelihoods because of it.

Reducing poverty in developing countries: a dilemma

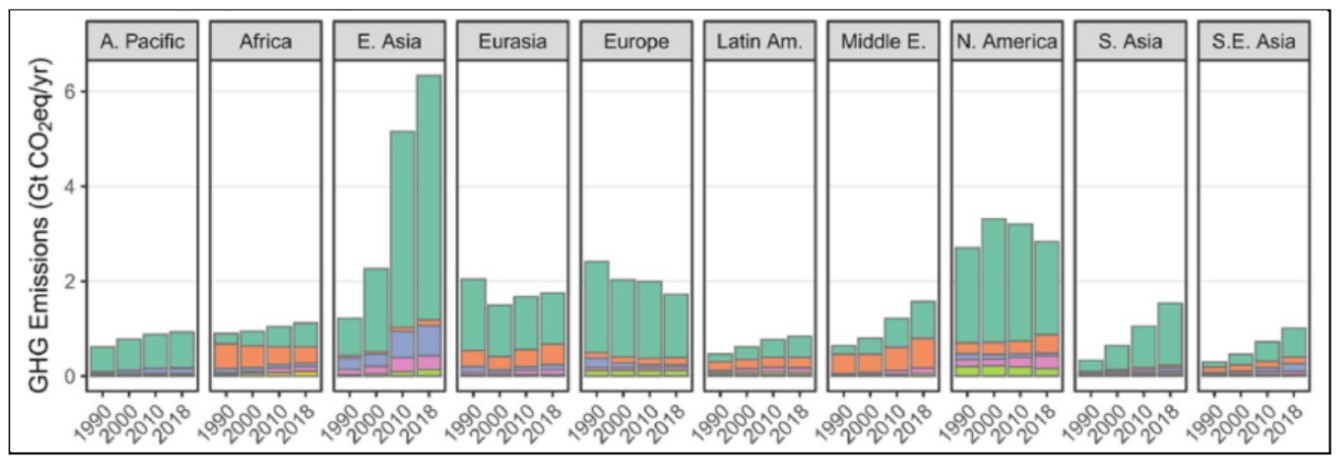

The climate crisis poses a dilemma for developing countries – on one hand, the old cut-and-dried method of growth and development are no longer feasible if warming are to be kept below 1.5°C. On the other hand, sustainable methods of development are also not without its problems – economic growth requires an ever increasing supply of energy – coal and gas power plants are a cheap and stable way to satisfy that energy need. Countries in Southern and Southeastern Asia showed the largest increase in the annual growth rate of carbon emissions from energy generation, 4.9% and 4.3% respectively between 2010 until 2018. Europe and North America are the only regions that saw a decrease in carbon emission from energy generation since the 2000s (Lamb et al., 2021).

Figure 8. Regional GHG emission from energy generation (Lamb et al., 2021)

Research by Jakob et al. (2020) explains that developing countries in South and Southeastern Asia tend to opt for coal power plants to satisfy their energy needs because it is an easy way to provide cheap electricity. Renewables have high capital costs when compared with coal because of country-specific frictions, coal is available domestically and new coal plants will spur growth in domestic coal mining that increases national revenue and reduces unemployment, and low political capital to adopt renewables as coal interests are ingrained in the government.

Incentive against sustainability

Socio-economic problems incentivise people in poverty, or people in general, to act unsustainably if they are required to do so. Research by Castilho et al. (2018) perfectly captures this phenomenon, residents living near conservation areas showed positive views on the preservation values that conservation areas are trying to achieve. However, they have negative attitudes to it because it hinders them from converting forests into agricultural fields – preventing them from work and limiting their livelihoods. In the end, a need for income prompted them to illegally deforestate.

Rising agricultural commodity prices also incentivise people to deforestate – increasing land-use change emissions as people are capitalizing on higher crop prices. It is shown that a one percent increase in the price index of agricultural commodities increases deforestation by 0.47 percent. Conservation zones are inadequate as it increases pressure and rivalry for the remaining open lands, accelerating deforestation in unprotected forests (Harding et al., 2021). This drive is also exacerbated by large markets such as the EU or China looking the other way on buying agricultural commodities produced on land that are illegally converted, providing a sense of legality and incentive for people to illegally convert land into palm oil plantations and the like (Lawson et al., 2014).

Conclusion

Climate change – however global – is a deeply unequal process where those that emit little and own little experience the worst. However, it does not mean that those affected the most will not contribute to climate change. We have seen that there is a convoluted relationship between climate change, poverty, and inequality. Ultimately, we have to realize that problem lies here and today. The crossroad between an equal and an unequal future does not lie in 2050 nor 2030, it lies today. Humanity can act to create a sustainable and equitable future in which every member of society can live a dignified life or they can squander that opportunity and suffer the long-term consequences, much of which would unequally be felt by those that already suffered to begin with.

References

Adams, H. (2016). Why populations persist: mobility, place attachment and climate change. Population and Environment, 37, 429–448. https://link.springer.com/content/pdf/10.1007/s11111-015-0246-3.pdf

Adger, W. N., Campos, R. S. d., Mortreux, C., & Gemenne, F. (2018). Mobility, displacement and migration, and their interactions with vulnerability and adaptation to environmental risks. In R. McLeman (Ed.), Routledge Handbook of Environmental Displacement and Migration (pp. 29-41). Taylor & Francis. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315638843

Adger, W. N., Crépin, A.-S., Folke, C., Ospina, D., Chapin, F. S., Segerson, K., Seto, K. C., Anderies, J. M., Barrett, S., Bennett, E. M., Daily, G., Elmqvist, T., Fischer, J., Kautsky, N., Levin, S. A., Shogren, J. F., van den Bergh, J., Walker, B., & Wilen, J. (2020). Urbanization, Migration, and Adaptation to Climate Change. One Earth, 3(4), 396-399. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S2590332220304851

Bathiany, S., Dakos, V., Scheffer, M., & Lenton, T. M. (2018). Climate models predict increasing temperature variability in poor countries. Science Advances, 4:eaar580. https://www.science.org/doi/epdf/10.1126/sciadv.aar5809

Carrington, D., & Taylor, M. (2022, May 11). Revealed: the ‘carbon bombs’ set to trigger catastrophic climate breakdown. The Guardian. Retrieved June 2, 2022, from https://www.theguardian.com/environment/ng-interactive/2022/may/11/fossil-fuel-carbon-bombs-climate-breakdown-oil-gas

Castilho, L. C., De Vleeschouwer, K. M., Milner-Gulland, E. J., & Schiavetti, A. (2018). Attitudes and Behaviors of Rural Residents Toward Different Motivations for Hunting and Deforestation in Protected Areas of the Northeastern Atlantic Forest, Brazil. Tropical Conservation Science, 11. https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/epub/10.1177/1940082917753507

EPA. (2021, June 30). Importance of Methane | US EPA. US Environmental Protection Agency. Retrieved May 26, 2022, from https://www.epa.gov/gmi/importance-methane

Farhat, S. (2020, January 21). Rising inequality affecting more than two-thirds of the globe, but it’s not inevitable: new UN report. UN News. Retrieved May 26, 2022, from https://news.un.org/en/story/2020/01/1055681

Hallegatte, S., Fay, M., & Barbier, E. B. (2018). Poverty and climate change: Introduction. Environment and Development Economics, 23(3), 217-233. https://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/environment-and-development-economics/article/poverty-and-climate-change-introduction/EAE3DA276184ED0DAEE6062E5DB0DB17

Hallegatte, S., & Rozenberg, J. (2017). Climate change through a poverty lens. Nature Climate Change, 7, 250–256. https://www.nature.com/articles/nclimate3253

Harding, T., Herzberg, J., & Kuralbayeva, K. (2021). Commodity prices and robust environmental regulation: Evidence from deforestation in Brazil. Journal of Environmental Economics and Management, 108. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0095069621000358

Horowitz, J. M., Igielnik, R., & Kochhar, R. (2020, January 9). Trends in US income and wealth inequality. Pew Research Center. Retrieved May 27, 2022, from https://www.pewresearch.org/social-trends/2020/01/09/trends-in-income-and-wealth-inequality/

Ingwersen, J. (2021, July 12). ‘Wither away and die:’ U.S. Pacific Northwest heat wave bakes wheat, fruit crops. Reuters. Retrieved May 30, 2022, from https://www.reuters.com/world/us/wither-away-die-us-pacific-northwest-heat-wave-bakes-wheat-fruit-crops-2021-07-12/

Islam, N., & Vos, R. (2015). Chapter 4. Insurance, Credit, and Safety Nets for the Poor in a World of Risk. In Financing for Overcoming Economic Insecurity (pp. 85-110). Bloomsbury Academic. https://www.bloomsburycollections.com/book/financing-for-overcoming-economic-insecurity/ch4-insurance-credit-and-safety-nets-for-the-poor-in-a-world-of-risk

Islam, S. N., & Winkel, J. (2017). Climate Change and Social Inequality. DESA Working Paper, (152). https://www.un.org/esa/desa/papers/2017/wp152_2017.pdf

Jakob, M., Flachsland, C., Steckel, J. C., & Urpelainen, J. (2020). Actors, objectives, context: A framework of the political economy of energy and climate policy applied to India, Indonesia, and Vietnam. Energy Research & Social Science, 70. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S2214629620303509

Lamb, W. F., Wiedmann, T., Pongratz, J., Andrew, R., Crippa, M., Olivier, J. G.J., Wiedenhofer, D., Mattioli, G., Khourdajie, A. A., House, J., & Pachauri, S. (2021). A review of trends and drivers of greenhouse gas emissions by sector from 1990 to 2018. Environmental Research Letters, 16(073005). https://iopscience.iop.org/article/10.1088/1748-9326/abee4e/pdf

Lawson, S., Blundell, A., Cabarle, B., Basik, N., Jenkins, M., & Canby, K. (2014). Consumer Goods and Deforestation: An Analysis of the Extent and Nature of Illegality in Forest Conversion for Agriculture and Timber Plantations. Forest Trends. https://www.forest-trends.org/wp-content/uploads/imported/for168-consumer-goods-and-deforestation-letter-14-0916-hr-no-crops_web-pdf.pdf

NOAA. (2022). Carbon Cycle Greenhouse Gases. Global Monitoring Laboratory – Carbon Cycle Greenhouse Gases. Retrieved May 26, 2022, from https://gml.noaa.gov/ccgg/trends/graph.html

NOAA. (2022, April 7). Increase in atmospheric methane set another record during 2021. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved May 26, 2022, from https://www.noaa.gov/news-release/increase-in-atmospheric-methane-set-another-record-during-2021

Oxfam & Stockholm Environment Institute. (2020, September). Confronting Carbon Inequality. Retrieved May 29, 2022, from https://oxfamilibrary.openrepository.com/bitstream/handle/10546/621052/mb-confronting-carbon-inequality-210920-en.pdf

Pretis, F., Schwarz, M., Tang, K., Haustein, K., & Allen, M. R. (2018). Uncertain impacts on economic growth when stabilizing global temperatures at 1.5°C or 2°C warming. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. A, 376:20160460. https://royalsocietypublishing.org/doi/pdf/10.1098/rsta.2016.0460

Teixidó-Figueras, J., Steinberger, J. K., Krausmann, F., Haberl, H., Wiedmann, T., Peters, G. P., Duro, J. A., & Kastner, T. (2016). International inequality of environmental pressures: Decomposition and comparative analysis. Ecological Indicators, 62, 163-173. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1470160X15006731

- (2021). The Sustainable Development Goals Report. UN. https://unstats.un.org/sdgs/report/2021/The-Sustainable-Development-Goals-Report-2021.pdf

- (2022). Progress towards the Sustainable Development Goals [Report of the Secretary-General]. UN. Retrieved May 28, 2022, from https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/content/documents/29858SG_SDG_Progress_Report_2022.pdf

UNEP. (2020, December). Emissions Gap Report 2020. UNEP. Retrieved May 29, 2022, from https://www.unep.org/emissions-gap-report-2020

Winsemius, H. C., Jongman, B., Veldkamp, T. I.E., Hallegatte, S., Bangalore, M., & Ward, P. J. (2018). Disaster risk, climate change, and poverty: Assessing the global exposure of poor people to floods and droughts. Environment and Development Economics, 23(3), 328-348. https://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/environment-and-development-economics/article/disaster-risk-climate-change-and-poverty-assessing-the-global-exposure-of-poor-people-to-floods-and-droughts/BEAFC2320176380B7B9296B60CE71BCD

WMO. (2022, May 24). Climate change made heatwaves in India and Pakistan “30 times more likely”. World Meteorological Organization |. Retrieved May 26, 2022, from https://public.wmo.int/en/media/news/climate-change-made-heatwaves-india-and-pakistan-30-times-more-likely

Wrathall, D. J., Hoek, J. V. D., Walters, A., & Devenish, A. (2018). Water Stress and Human Migration: A Global, Georeferenced Review of Empirical Research. Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. https://reliefweb.int/sites/reliefweb.int/files/resources/I8867EN.pdf