Devin Nuranggaputra Ramadhani (1), Caroline Velenthio Amansyah (1), Aushaaf Rafif Keane Pribadi (1), Nawfal Aulia Luthfurrahman (1), Atha Bintang Wahyu Mawardi (1)

(1) Ilmu Ekonomi, Fakultas Ekonomika dan Bisnis, Universitas Gadjah Mada, Indonesia

1. INTRODUCTION

In financial markets, bond yield is a critical metric that reflects the return an investor can expect from holding a bond until maturity. It serves not only as an indicator of potential returns but also as a tool for forecasting market expectations regarding future economic conditions (Altavilla et al., 2013). Given its significance, understanding the determinants of bond yields, especially in emerging markets like Indonesia, is crucial for both investors and policymakers. Previous studies have extensively explored the relationship between macroeconomic factors and bond yields, with a particular focus on government bonds (Gadanecz et al., 2018). However, there is a noticeable gap in the literature when it comes to corporate bond yields, particularly in emerging markets like Indonesia. Corporate bonds, which carry unique risks such as credit risk, are more sensitive to macroeconomic conditions and firm-specific factors, making them a compelling subject for deeper analysis.

For instance, several studies have examined the impact of the central bank’s policy rate, such as the BI Rate, on bond yields, finding a generally positive correlation (Mahirun et al., 2023; Yuliana, 2016; Sundoro, 2018). However, these studies often do not delve into the specific dynamics of corporate bonds, which may react differently to monetary policy due to their higher risk profile. Moreover, the relationship between bond yields and the output gap—a measure of the difference between actual and potential GDP—remains underexplored in the context of corporate bonds. Ludvigson & Ng (2009) suggest that bond yields behave countercyclically, indicating an inverse relationship with the output gap. Yet, this finding is predominantly based on government bonds, leaving room for investigation into how corporate bonds might respond differently.

Inflation is another macroeconomic variable with debated effects on bond yields. While some studies identify a positive relationship between inflation and corporate bond yields (Surya & Nasher, 2011), others find no significant impact (Kusriyanto & Nelmida, 2019). This inconsistency suggests a need for further research, particularly in the context of emerging markets. Lastly, the impact of exchange rates on bond yields adds another layer of complexity. Research by Hoffman et al. (2020) indicates an inverse relationship between local currency appreciation and bond yields. However, the specific effects on corporate bond yields, as opposed to government bonds, have not been thoroughly examined, particularly in Indonesia’s volatile market.

To address these gaps, this study will focus on the long-term and short-term effects of key macroeconomic variables—namely the BI rate, output gap, inflation rate, and exchange rate—on corporate bond yields in Indonesia. Utilizing advanced econometric techniques, specifically the Autoregressive Distributed Lag (ARDL) bounds test approach (Pesaran et al., 2001), this research aims to provide a more nuanced understanding of these relationships. By filling these gaps in the literature, this study seeks to contribute valuable insights into the determinants of corporate bond yields in emerging markets. The findings are expected to offer practical tools for better investment strategies and policy decisions, ultimately promoting more stable and efficient financial markets in Indonesia and similar contexts.

2. LITERATURE REVIEW

Theoretical Framework on Bond Yield Determinants

There are several market-specific and macroeconomic factors that shape bond yield determinants. Corporate bond yield spreads, for instance, are well-known indicators of both credit risk and broader economic conditions (Kim et al., 2020). These spreads reflect the risk of lending to companies and represent compensation for investors who take on credit and market risks. The interaction of these factors helps explain how bond yields react to changing economic conditions. Key determinants include credit risk, macroeconomic fundamentals, market liquidity, global financial integration, and interest rate structures.

Credit risk is a major factor in bond yields, as bonds with higher default risks tend to have wider yield spreads. Lower credit ratings, indicating higher default risk, lead investors to demand higher yields as compensation (Karlsson & Österholm, 2020). This stable relationship between credit spreads and GDP growth holds even in times of financial turbulence (Karlsson & Österholm, 2020). However, in economic downturns, bond yields become more sensitive to credit risk. For example, equity volatility rises during financial crises, and the associated increase in bond yield spreads reflects the higher risk premium investors demand (Kim et al., 2020). Understanding credit risk is crucial for assessing bond yield behaviour during times of financial instability.

Macroeconomic factors, such as inflation, interest rates, and economic growth, also influence bond yields. Inflation expectations are closely tied to bond yields, as investors adjust their required returns based on anticipated changes in purchasing power. Yield spreads reflect these expectations and the market’s outlook on future monetary policy (Simović et al., 2016). Central bank policies, especially unconventional interventions like quantitative easing, impact bond yields by affecting market liquidity (Kim et al., 2020). Additionally, interest rate volatility leads to wider yield spreads as investors seek compensation for uncertainty in future rate movements (Kim et al., 2020). These macroeconomic factors directly affect bond pricing by altering perceptions of risk and return.

Market liquidity is another important determinant of bond yield spreads. Less frequently traded bonds or those with smaller issuance sizes carry a liquidity premium, as investors need compensation for potential difficulty selling them in secondary markets. This is particularly relevant in the corporate bond market, where liquidity constraints can drive yield spreads higher (Simović et al., 2016). During financial crises, liquidity premiums widen as market liquidity dries up, pushing bond yields higher (Kim, Kim & Jung, 2020). Therefore, understanding market liquidity dynamics is critical when assessing bond yields, especially for corporate bonds with lower liquidity profilesGlobal financial integration also plays a key role, particularly in sovereign bond markets. Sovereign bonds in post-transition European economies show varying levels of integration with Eurozone bonds, and this integration is influenced by both global risk factors and domestic economic conditions (Simović et al., 2016). During global financial stress, such as the 2008 crisis, bond markets in these countries become more isolated from global benchmarks like German bonds, leading to wider yield spreads. This reflects increased uncertainty and risk perceived by investors, who demand higher yields as compensation (Simović et al., 2016). Thus, global financial integration is important in understanding sovereign bond yield behavior, especially in smaller, less developed markets.

The structure of interest rates, particularly the slope of the yield curve, is also a strong predictor of bond yields. The yield curve’s slope, typically the difference between short-term and long-term interest rates, reflects market expectations of future economic conditions. A steep yield curve indicates expectations of strong economic growth and rising inflation, leading to narrower yield spreads as investors feel more optimistic (Karlsson & Österholm, 2020). Conversely, a flattening or inverted yield curve, where long-term rates fall relative to short-term rates, signals economic distress, prompting investors to demand higher risk premiums and wider yield spreads (Karlsson & Österholm, 2020). The yield curve provides insights into future economic conditions and their impact on bond yields.

In conclusion, bond yields are shaped by credit risk, macroeconomic factors, market liquidity, global integration, and interest rate structures. These factors influence investor perceptions of risk and return, determining yield spreads that compensate for those risks. Understanding these relationships is crucial for investors and policymakers, particularly during times of economic uncertainty or financial stress.

BI Rate and Corporate Bond Yield (positively related)

BI Rate refers to the interest rate issued by Bank Indonesia as an indicator of monetary policy. BI rate is a benchmark for debt interest expense calculation and an instrument to determine the cost of credit as well as deposit rates in the financial system (Nurwulandari, 2021). Changes in the BI rate will also influence market interest rates and may affect bond prices as well, subsequently changing a commodity yield. According to Ang (1997), when market interest rates are on the rise, bond prices typically fall, leading to higher yields since investors want returns commensurate with their new borrowing cost. As a result, the BI rate, which affects market yield, often has a positive correlation with bond yields.

A number of studies have consistently reported a relationship between these factors. Mahirun et al. (2023) reported a significantly detrimental effect of the BI rate on interest rates in corporate bonds using Indonesian data. This result indicates that as the BI rate increases, investors raise their return forecasts on corporate bonds to meet the rising cost of capital, pushing yields up. Yuliana (2016) emphasized that BI rate adjustments greatly affect the government and corporate bond markets, as the yields seem sensitive to changes in BI rates. Sundoro (2018) also explains that in times of increasing interest rates, bond investors require higher yields to cover inflationary pressures and currency depreciation risks.

In addition, the BI Rate does not stand alone but interacts with related macroeconomic variables. Hoffman et al. (2020) suggests that exchange rate volatility can amplify the effect on bond yields if BI rate differentials rise in emerging markets like Indonesia. For example, when the BI rate rises, a strong domestic currency can entice overseas capital to local bonds, yanking bond yields higher as demand surges. The triangular relationship between the BI rate, exchange rates, and inflation expectations is crucial for a comprehensive analysis of bond yield movements. Moreover, Kusriyanto and Nelmida (2019) stated that the impact of the BI rate on bond yields is influenced by investors’ perceptions and market conditions. In periods of lackluster economic growth, even a small BI rate increase can quickly pressure bond yields to rise, especially when financial-sector risk aversion is high. This is particularly relevant to Indonesia, where changes in domestic monetary policy can be reinforced by global implications.

Output Gap and Corporate Bond Yield (inversely related)

Output gap is defined as the difference between the actual output of an economy and the optimum potential output of an economy in a specific period of time. Output gap is an important indicator of economic conditions which also shows the fluctuation of the business cycle (Eertman, 2018). As output gap is one of the variables that can represent macroeconomic conditions, it has a potential role in predicting the movement of bond yield. Ludvigson & Ng (2009) highlight that bond yield has a strong countercyclical component. Recessions and expansions influence bond risk premia which then affect bond yield. This study argues that investors must be compensated for risk related to recessions, or conversely, require lower risk premia for time of expansions. However, as the study used a large number of macroeconomic variables, it is hard to identify a specific indicator which is the most useful in predicting bond yield. Therefore, it is interesting to investigate whether output gap, as one of the representative macroeconomic indicators, can be a good predictor of bond yield.

The link between the output gap and bond yields goes back to larger market narratives about how economic conditions influence investor sentiment. A negative output gap, where actual output falls below potential, typically signals slower future growth, leading investors to seek safer assets like bonds. This drives bond prices up and yields down. A negative output gap tends to keep inflation low and puts downward pressure on bond yields, while a positive output gap, signaling an overheated economy, can fuel inflation, prompting central banks to raise interest rates, thereby increasing bond yields. Orphanides and Van Norden (2002) found that output gap estimates are central to understanding bond yield dynamics, particularly in times of economic uncertainty.

Additionally, Gali and Gertler (2007) argue that the output gap is a critical variable in explaining interest rates and bond yields through its effect on inflation expectations. In periods of negative output gaps, inflation tends to stay low, allowing central banks to keep interest rates down, which suppresses bond yields. On the other hand, positive output gaps tend to lead to inflationary pressures, driving bond yields higher as investors demand greater returns to compensate for future inflation. Clarida, Galí, and Gertler (1999) emphasized that the relationship between the output gap and bond yields is a key channel through which central bank policy impacts financial markets.

Investor risk sentiment also plays a crucial role in the interaction between the output gap and bond yields. Ludvigson and Ng (2009) noted that economic expansion reduces investor risk premiums, leading to lower bond yields. Conversely, during recessions or periods of negative output gaps, bond investors demand higher risk premiums to compensate for increased risks such as defaults. Bekaert, Hoerova, and Duca (2013) found that bond yields tend to rise when perceived risks are higher, particularly during periods of negative output gaps when recession fears are heightened.

Empirical studies support the idea that the output gap can serve as a predictor of bond yields. For example, Estrella and Mishkin (1998) showed that the output gap, along with other macroeconomic variables like the term spread and inflation, can be used to forecast bond yields. However, they also noted that the output gap alone may not be sufficient and should be considered alongside other indicators. More recent studies, such as those by Stock and Watson (2012), emphasized that incorporating a broad set of macroeconomic variables can improve the accuracy of bond yield forecasts, reflecting the multidimensional nature of the economy.

Inflation Rate and Corporate Bond Yield (positively related/contradictory finding)

Nurfauziah & Setyarini (2004) highlighted that inflation increases uncertainty in the bond market, prompting investors to demand higher yields as compensation for the increased risk. Surya & Nasher (2011) confirmed this positive relationship between inflation and corporate bond yields in their study. In contrast, Kusriyanto & Nelmilda (2019) found no significant impact of inflation on yield to maturity, suggesting the relationship may vary in the short term. This suggests that inflation has greater and more lasting effects that might be understated in short-term analysis. Inflation may take time to affect bond yields, as central bank interventions or temporary economic shocks can mitigate its impact.

Other studies, such as Kusumaningrum et al. (2019), emphasize that the influence of inflation on bond yields may be more pronounced in the long run, underscoring the need for further exploration into long-run cointegration to resolve these contradictory findings.

However, in the long term, inflation becomes more impactful as it gradually erodes the purchasing power of bond returns. Investors start demanding higher yields to compensate for this inflation risk, especially for bonds with longer maturities, which are more vulnerable to real value loss. Persistent inflation, therefore, leads to a noticeable and substantial increase in bond yields. This aligns with the inflation risk premium theory, where bondholders require higher compensation for the uncertainty inflation introduces over time (Nurfauziah & Setyarini, 2004; Surya & Nasher, 2011).

Furthermore, the long-term effects of inflation are better captured through cointegration analysis, a method used to examine long-term dynamics. It shows that inflation and bond yields tend to move together over time, smoothing out short-term volatility. Thus, while the short-term relationship between inflation and bond yields might appear weak or contradictory, the long-term impact becomes clearer, reinforcing the idea that inflation plays a significant role in determining bond yields over extended periods (Kusumaningrum et al., 2019).

Exchange Rate and Corporate Bond Yield (inversely related)

Hartono (2009) maintained that an appreciation in domestic currency increases bond prices and thus reduces bond yields. Similarly, Hoffman et al. (2020) highlighted the role of changes in local credit risk premiums in shaping the negative relationship between local currency value and bond yields. In addition, studies by Kim and Yang (2011) and Diebold et al. (2006) support this view, showing that currency appreciations signal stronger domestic economies, leading to lower risk premiums and bond yields. Furthermore, Li et al. (2018) concluded that short-term international capital movements also affect the relationship between exchange rates and bond yields, indicating a time-varying impact of exchange rate fluctuations on bond market performance.

The connection between bond yields and exchange rates has been explored extensively, with many works highlighting the vital role of economic conditions. Gyntelberg and Remolona (2013) demonstrated that currency volatility is a significant determinant of bond yields, particularly in emerging markets, where exchange rate movements strongly affect investor risk perception. Short-term capital inflows often influence this dynamic, as Li et al. (2018) showed, indicating that exchange rate fluctuations have direct and indirect impacts on bond markets. Similarly, Combes, Kinda, and Plane (2012) found that capital inflows into local currency bond markets often coincide with a strengthening of the local currency, reflecting increased confidence in the issuing country’s economic stability.

In addition to credit risk premiums, inflation expectations also play a crucial role in linking exchange rates and bond yields. Arslanalp and Tsuda (2014) demonstrated that currency appreciations lower inflation expectations, reducing nominal bond yields. This transmission mechanism supports the view that currency strength drives yields lower through multiple channels, including inflationary pressure. Likewise, Sarno and Taylor (1999) found that capital inflows driven by anticipated currency appreciation help to suppress inflation and strengthen bond markets, particularly in emerging economies.

3. DATA AND METHODOLOGY

Data used in this research are secondary data compiled from Bank of Indonesia, Badan Pusat Statistik (BPS) Indonesia, Federal Reserve Economic Data (FRED), and Penilai Harga Efek Indonesia (PHEI). The samples are comprised of quarterly time series macroeconomic and financial data in Indonesia from 2011 – 2023, amounting to 52 observations.

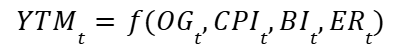

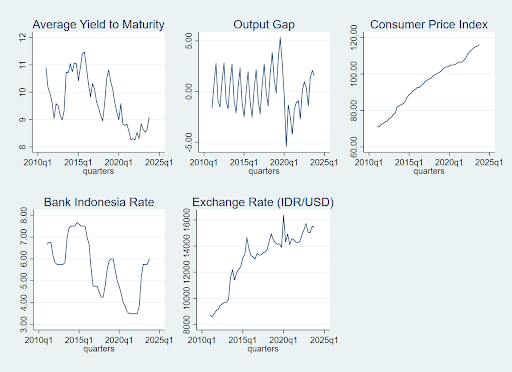

To estimate the effect of macroeconomic variables on bond yield, cointegration employing Autoregressive Distributed Lag (ARDL) bounds test from Pesaran et al. (2001) is used. This method can accommodate long-term and short-term estimates simultaneously. ARDL is suitable for time series analysis with small sample size and combination of data integrated of order zero, I(0), and of order one, I(1). The general model equation is defined below.

Where YTM is Corporate Yield to Maturity (YTM) using the average corporate bond yield across ratings and maturities; OG is output gap calculated from Hodrick-Prescott Method by Hodric & Prescott (1997); CPI shows inflation using Consumer Price Index; BI is Bank Indonesia Rate; and ER is exchange rate presented in IDR/USD. The specific ARDL model is specified below.

Where Δ is first difference; 𝛿1 is constant; ∂1, ∂2, ∂3, ∂4 refer to long-term parameters; ⍺i, 𝛽i, ⍵i, 𝛾i refer to short-term parameters; and 𝜀 is residuals.

4. RESULT AND DISCUSSION

4.1. Diagnostic and Stability Test

[row ]

[col span=”1/2″ ]

Diagnostic Test

Jarque-Bera Normality Test

Breusch-Pagan Test for Heteroskedasticity

Breusch–Godfrey LM Test for Autocorrelation

Ramsey RESET Test

[/col]

[col span=”1/2″ ]

Results

Prob(Chi-Squared): 0.1712

Prob(Chi-Squared): 0.6194

Prob(Chi-Squared): 0.1727

Prob(F-Stat): 0.4275

[/col]

[/row]

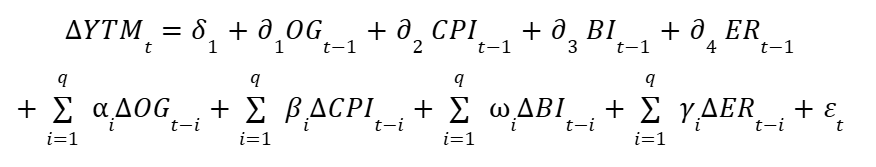

Figure 1. CUSUM Stability Test for Yield to Maturity

Table 1 shows the result of diagnostic tests. The data and model are clear of heteroskedasticity, autocorrelation, and misspecification issues. Residuals are normally distributed. CUSUM test in Figure 2 is used to check the model stability. The statistics reside inside the 5% significance level, indicating that there is no significant deviation during the period of the data.

4.2. The Movement of Yield to Maturity and Macroeconomic Variables

Table 2. Descriptive Statistics

[row ]

[col span=”1/6″ ]

Variable

Obs.

Mean

Median

Minimum

Maximum

Std. Dev.

Skewness

Kurtosis

Jarque-Bera

Probability

[/col]

[col span=”1/6″ ]

YTM

52

9.687957

9.583379

556565

11.47465

0.929063

.1990679

1.846885

3.224

.1994

[/col]

[col span=”1/6″ ]

OG

52

0.045203

-.0513737

-5.46694

5.330853

2.120277

.0156403

2.961436

.0053

.9973

[/col]

[col span=”1/6″ ]

CPI

52

94.81455

96.94757

70.98111

116.0933

13.42133

-.2823417

1.939407

3.128

.2093

[/col]

[col span=”1/6″ ]

BI

52

5.597756

5.75

3.5

7.666667

1.315829

-.0485501

1.924298

2.528

.2826

[/col]

[col span=”1/6″ ]

ER

52

13049.98

13652

8597

16367

2123.289

-.8455813

2.542785

6.65

.036

[/col]

[/row]

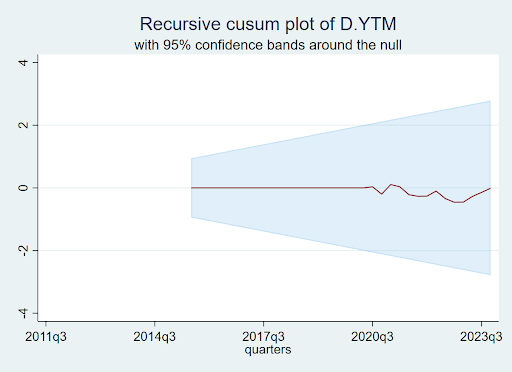

Figure 2 shows the trend of yield to maturity (YTM), output gap (OG), consumer price index (CPI), BI rate (BI), and exchange rate (ER) in 2011 – 2023. Table 1 presents the descriptive statistics of the variables. Relatively similar values of mean and median indicating symmetric distribution of the data around the central point. However, ranges and standard deviations reveal that the variables are quite volatile, especially ER and CPI. Although, these results are still under expectation because the period used are long and contain Covid-19 economic shock. Variables YTM, OG, CPI, and BI have skewness values below the range of -0.5 to 0.5 indicating fairly symmetrical data. However, the skewness of variable ER is -0.845 suggesting a moderate negative skewness, but still under the range of -1 to 1. The kurtosis values of the variables are below 3 indicating platykurtic distribution, slightly flatter than normal distribution. The Jarque-Bera statistics signify normality for YTM, OG, CPI, and BI. On the other hand, the result for variable ER shows that the data is not normally distributed. Nevertheless, as is discussed in the diagnostic test, residuals of the model are normally distributed.

Figure 2. Trend Line of Yield to Maturity, Output Gap, Consumer Price Index, BI Rate and Exchange Rate

4.3. Determining Optimal Lag and Unit Root Test of Aggregate Bond Yield

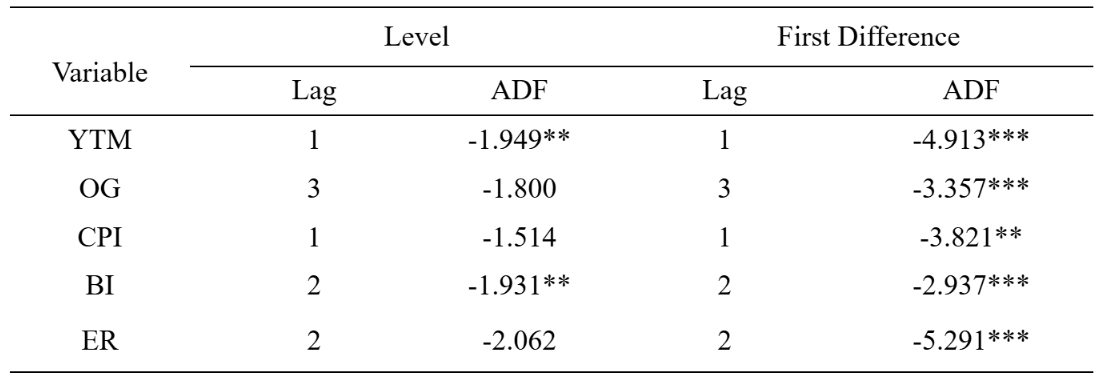

Table 3. ADF Unit Roots Test for The Level and The First Differences

*, **, and *** show significance at level 10%, 5%, and 1%, respectively.

Before estimating the ARDL, checking the stationarity of the time series variables is important. Not only non-stationarity can result in spurious regression, the model of ARDL itself can only be used for data integrated of order zero, I(0), and of order one, I(1). Augmented Dickey-Fuller (ADF) unit root test is used to check for stationarity in Table 2. The results show that variables YTM and BI are integrated of order zero (stationer) and variables OG, CPI, and ER are integrated of order one (non-stationer). Hence, ARDL is suitable in this analysis.

Lag optimal is vital because it can influence the standard error, thus affecting the estimation inference (Harris, 1995). Lag optimal of the ARDL is taken from the lowest value of the optimum lag proposed by Akaike Information Criterion (AIC), Schwarz Information Criterion (SIC), and Hannan-Quinn (HQ). The optimum lag chosen is ARDL (1 3 1 2 2) model.

4.4. Estimation Results

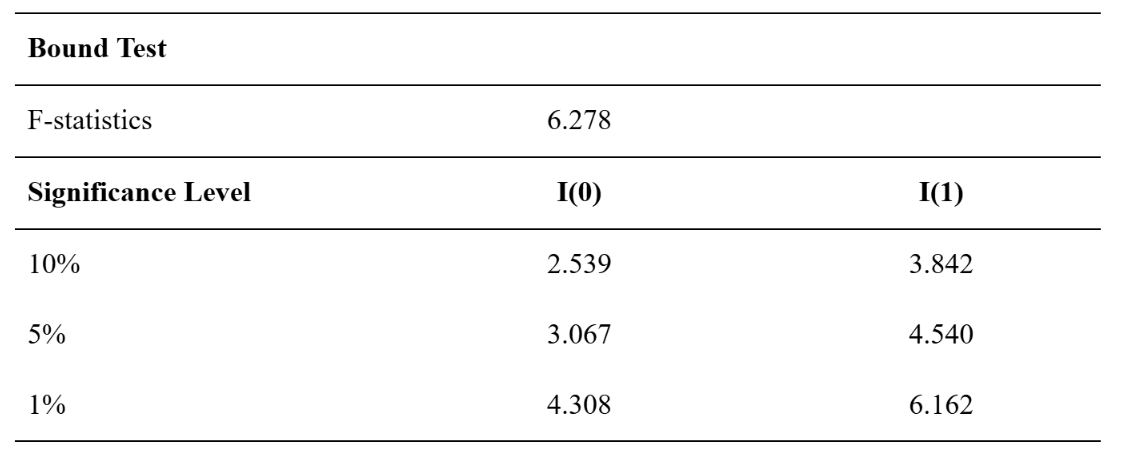

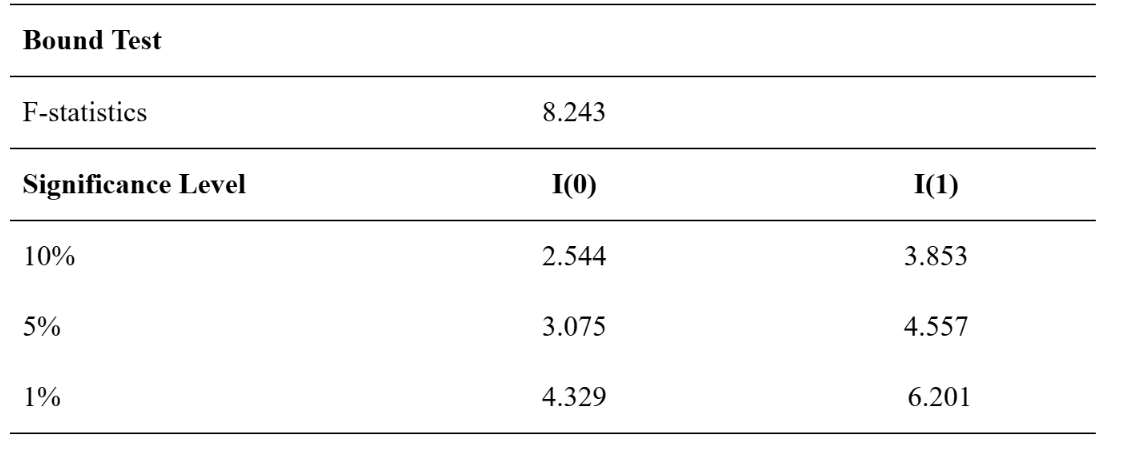

Table 4. ARDL Bounds Test Result

Cointegration bound-test from Pesaran et al. (2001) is employed to analyse long-run relationships. Result in Table 3 shows F-statistic of 6.278 which is higher than the upper-bound critical value of 6.162 in 1% significance level. The error correction term is negative, below absolute 1, and significant. This indicates that there is cointegration between yield to maturity, output gap, consumer price index, BI rate, and exchange rate.

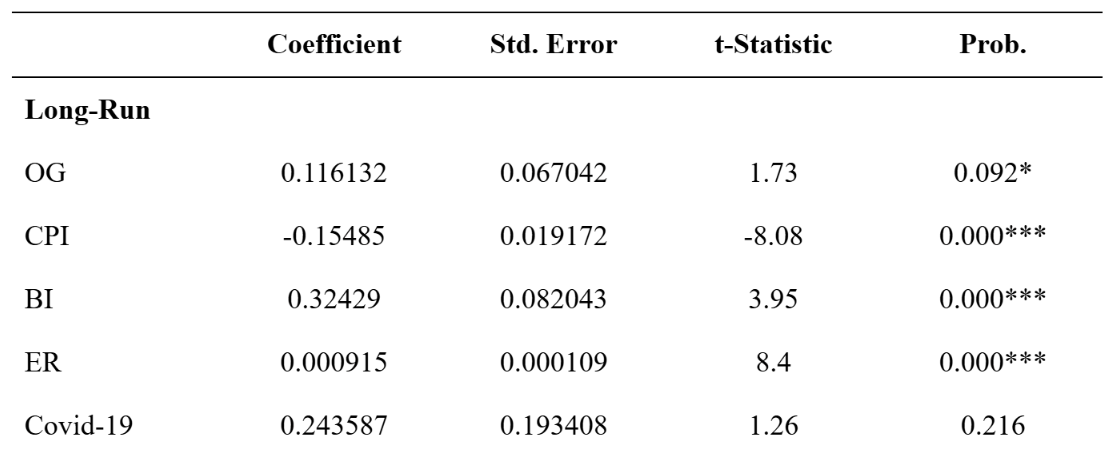

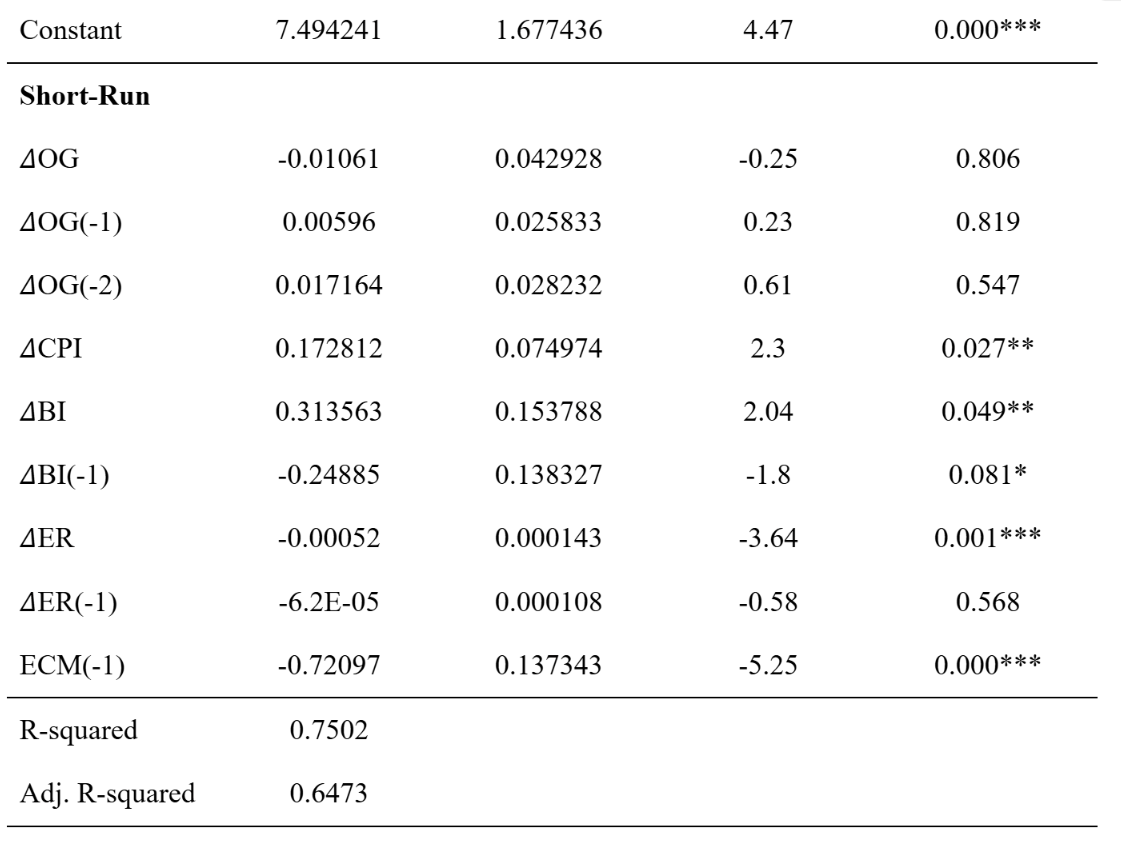

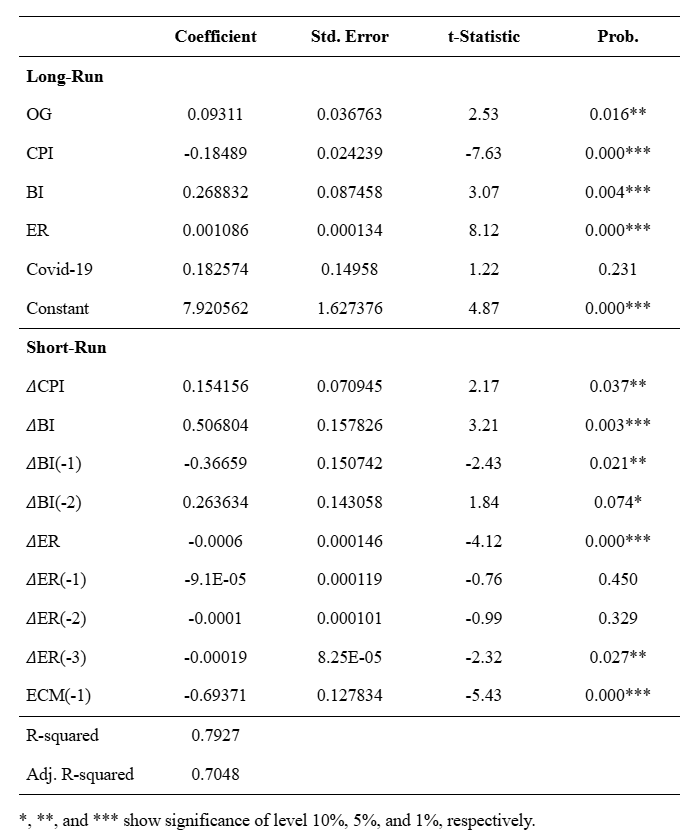

Table 5. Long-Run and Short-Run Estimation Results

*, **, and *** show significance of level 10%, 5%, and 1%, respectively.

Afterwards, long-run and short-run coefficients of the ARDL are estimated in Table 5. The results show that consumer price index (CPI) as a proxy of inflation has a statistically significant relationship with corporate bond yield in the long run and the short run. The short run impact suggests that an increase in CPI leads to higher corporate bond yield. This result is consistent with the previous researches findings for the case of bond yield in banking companies (Mahirun et al., 2023) and sovereign bond yield (Yusuf & Prasetyo, 2019; Hsing, 2015). In the short run, inflationary pressure increases risk associated with corporate bonds, resulting in higher yield to compensate for risk. On the other hand, the long run impact shows a negative impact of CPI on corporate bond yield. This result is in line with Ślusarczyk et al. (2020) and Zhou (2021), where despite short-run positive impact of inflation on government bond yield, negative long-run impact is observed. Although their studies focused on government bond yield, the characteristics of corporate bonds should be similar if not more sensitive to inflationary pressure. This inverse relationship may be explained by the negative impact of inflation on long run economic growth (Zhou, 2021). Lower CPI signals stable economic conditions which may drive growth in the long run. Higher potential growth results in higher paying interest rates which then lead to increased bond yield (Poghosyan, 2014).

The results also indicate a negative impact of exchange rate on corporate bond yield in the short run and a positive impact on the long run. The short run relationship implies that appreciation of domestic currency leads to increased bond yield. This finding is in line with Kurniasih & Restika (2015) in the case of Indonesia government bond yield. One possible explanation is that appreciation of domestic currency or instead depreciation of foreign currency will result in capital loss for foreign investors. This leads to lower demand for bonds which decreases bond price, resulting in higher bond yield. Meanwhile, our long run finding indicates that an appreciation of domestic currency results in lower corporate bond yield. This result is consistent with the findings of Zhou (2021), Ślusarczyk et al. (2020), and Qisthina et al. (2022). The negative impact of domestic currency appreciation on bond yield may be attributed to the decrease in domestic currency credit risk premium (Hoffman et al., 2020). Domestic currency credit risk premium is defined as the additional return expected for the risk of investing in local currency bonds, compared to relatively risk-free US bonds. In other way, as the local currency appreciates, domestic economic condition is perceived to be stronger, thus reducing the risk of investing in local currency bonds, which is reflected in a decrease in domestic currency credit risk premium. As the risk associated with investing in local currency bonds decreases, global investors are willing to accept lower yield as compensation. This difference between short-run and long-run relationships may be due to capital gain being the strongest driver in the transaction of corporate bonds for foreign investors in the short run. Meanwhile, investors may consider currency credit risk premium as a more important determinant in the long run.

Meanwhile, an analysis of output gap (OG) and the BI rate based on the provided estimation results reveals distinct dynamics in both the long and short run. In the long run, the output gap exhibits a positive but marginally significant effect (p = 0.092) on the dependent variable, likely indicating that as the economy operates above its potential (a positive output gap), there is a modest upward pressure on the variable in question. This finding is consistent with more recent studies that suggest output gaps can influence economic variables such as inflation and interest rates, albeit with varying degrees of impact depending on the economic environment. For instance, studies like those by Christiano et al. (2015) and Ramey (2016) discuss how output gaps can serve as indicators of economic slack, influencing central bank policies and, consequently, broader economic outcomes. However, the weak significance level suggests that in this context, the output gap may not be the most dominant factor, especially when compared to other macroeconomic variables.

On the other hand, the BI rate shows a strong and highly significant positive relationship with the dependent variable in the long run (p < 0.01). This indicates that an increase in the BI rate leads to a substantial increase in the dependent variable, which is consistent with the role of central bank rates as a primary tool in influencing economic conditions. Recent literature supports this finding, highlighting how central bank rates directly impact interest rates across the economy, influencing investment, consumption, and ultimately, economic growth (Cochrane, 2018; Nakamura & Steinsson, 2018). The robust significance of the BI rate in this context underscores its critical role in monetary policy transmission mechanisms, where changes in the central bank’s policy rate are effectively transmitted through financial markets and impact broader economic variables.

In the short run, the output gap’s coefficients, including its lagged values, do not show significant effects, suggesting that short-term fluctuations in the output gap are not influential in this model. This could be due to the fact that short-term economic dynamics are often dominated by more immediate shocks or policy actions, rather than the output gap itself. Recent studies by Gali (2020) and Del Negro et al. (2020) indicate that short-term economic variables often respond more to unexpected shocks, such as sudden changes in demand or supply conditions, than to the output gap, which may explain the lack of significance in this case.

The BI rate, however, shows a different pattern in the short run. The immediate impact of changes in the BI rate (ΔBI) is positive and significant at the 5% level, indicating that a rise in the BI rate quickly translates into an increase in the dependent variable. This aligns with the findings of recent studies, such as those by Jorda et al. (2020), which demonstrate that interest rate changes can have immediate effects on financial markets and economic conditions. The lagged effect of the BI rate (ΔBI(-1)) is negative and significant at the 10% level, suggesting that while an initial increase in the BI rate raises the dependent variable, this effect may be partially offset in subsequent periods, potentially due to adjustments in market expectations or the rebalancing of portfolios by investors.

4.5. Robustness Check with AIC and BIC Lag Optimal

One principal issue in cointegration testing is its sensitivity to lag length selection (Ghouse et al., 2018). Misspecification in the leg length can lead to unreliable cointegration results. Hence, to check whether the results are robust, we evaluate the consistency of the results under different lag optimal choices. In this case, AIC and BIC optimal lag selections are employed for the ARDL model.

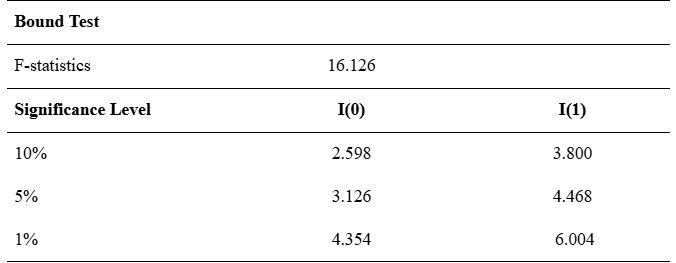

Table 6. ARDL Bounds Test Result with Lag Optimum AIC of ARDL(1 0 1 3 4)

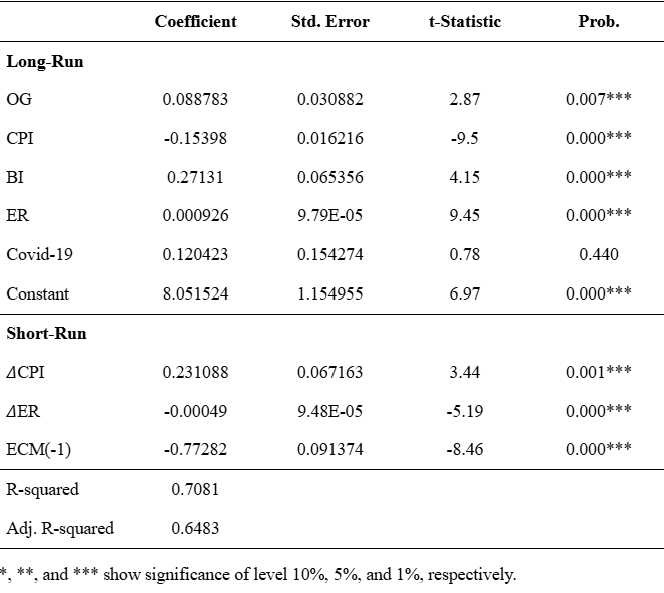

Table 7. Long-Run and Short-Run Estimation Results for AIC Lag Selection

The result of bounds test using ARDL(1 0 1 3 4) from AIC optimal leg length is significant, indicating cointegration in 1% level of significance. The error correction term is negative, below absolute 1, and statistically significant. The long-run estimation results are consistent with our main ARDL(1 3 1 2 2) model, with variables OG, CPI, BI, and ER having statistically significant long-run impact on YTM, each showing the same sign as the previous model. Results of the short-run estimation also show consistency with generally the same relationship directions. The differences lie in the impact of BI which accommodates the positive effect of BI rate in the previous 2 years on current corporate bond yield; also the impact of ER which accommodates the negative effect of exchange rate in the previous 3 years on current corporate bond yield.

Table 8. ARDL Bounds Test Result with Lag Optimum BIC of ARDL(1 0 1 0 1)

Table 9. Long-Run and Short-Run Estimation Results for BIC Lag Selection

The F-statistics of bounds test using ARDL(1 0 1 0 1) from BIC optimal leg length is statistically significant, indicating cointegration in 1% level of significance. The error correction term is also negative, below absolute 1, and statistically significant. The long-run result is statistically significant for all variables OG, CPI, BI, and ER, with the same coefficient sign as the AIC and main model. The short-run results which only show the effects of CPI and ER are statistically significant, also with the same relationship directions as the previous models. Variables OG and BI have lag optimum of zero due to BIC inclination to select a more parsimonious model (Kripfganz & Schneider, 2023).

Overall, bounds test and ARDL estimations using AIC and BIC lag selection indicate consistent results with our main model. Therefore, the results of cointegration and long-run/short-run estimations for YTM, OG, CPI, BI, and ER are robust.

5. CONCLUSION

By showcasing how inflation, the base interest rate (BI rate), exchange rates, and output gap impact yield fluctuations, it plays a pivotal role in delivering conclusive evidence of empirical discoveries concerning the correlation between macroeconomic factors and corporate bond yields in Indonesia. The research supported the notion that investors are greatly swayed by inflation expectations in their actions and can profoundly affect both the erosion of investor purchasing power and the anticipation of interest rates. This, in turn, signifies that corporate bond yields may increase by 0.17% for every 1% uptick in inflation in the short term when investors foresee higher inflation and demand a premium to counteract the diminishing real value of bond returns. This process acts as a safeguard that anchors the bond market from becoming overly binary, but only if inflation expectations could be more subdued to prevent excessive fluctuations.

Another association that inflation management holds is with investor confidence. Lower risk premiums and reduced bond yields—controlled inflation led to enhanced investor sentiment. Monetary policy holds significant sway as benchmark rates are allowed to fluctuate. Given the close link between decreasing rates and inflation anticipations, policymakers should seek more formal mechanisms such as recommitment to an inflation targeting law. For instance, proactive rate hikes when inflation is on the rise or credible forward guidance to shape expectations in financial and real sector markets. This could, in turn, promote market stability, enabling others to invest at lower bond yields over time, particularly if the target inflation rate falls within the 2–3 percent range.

Research on the impact of the BI rate on bond yields reinforces the importance of monetary policy channels in shaping interest rates for corporate borrowing costs. Our analysis indicates a substantial response—a 1% increase in the BI rate results in a 0.32% hike in corporate bond yields. Consequently, policymakers should strive to strike a balance between controlling inflation and the increased corporate financing expenses from a BI rate increase that could deter investment and subsequently economic growth. Progressing gradually with BI rate adjustments, coupled with transparency, could help avert sharp surges in bond yields and bolster foreign investor confidence.

Furthermore, the exchange rate has a dual effect on determining bond yields. In the medium term, currency appreciation leads to yield spikes, as foreign investors perceive that escalating asset values in bonds could drive up demand. However, a stronger currency in the long term would eventually reduce the domestic credit risk premium, resulting in cheaper corporate bond yields. This interconnection underscores the importance of stable exchange rates as part of a broader economic strategy, particularly in emerging economies like Indonesia, where foreign capital flows are highly sensitive to currency fluctuations. This may involve policy interventions in the exchange rate to mitigate excessive volatility (and consequently the risk premia demanded by foreign investors) and stabilize yields in the long haul.

From a policy standpoint, our findings suggest that Indonesia would benefit from a more cohesive approach to its monetary policy, which incorporates aligning BI rate adjustments with inflation targeting and the effect on exchange rate management to establish a consistent monetary policy that also minimizes spill-overs between these macroeconomic components. Effective inflation control, accompanied by Bank Indonesia’s judicious management of its key rate and further currency stabilization, should help keep bond yields in check and provide a foundation for corporate and broader growth.

However, the study had its constraints, which are vital for researchers to consider. While offering profound global insights into the robust relationship between macroeconomic factors and bond yields, we have not specifically tackled this across different maturity levels or credit ratings. Fine-tuning in terms of analyzing yields in different types of bonds could prove beneficial. Additionally, the analysis did not fully account for structural breaks (e.g., major economic upheavals like COVID-19), which could have impacted the correlation between bond yield dynamics during crisis periods. It is hoped that in future studies, these factors will be rigorously addressed for a deeper and more comprehensive understanding of the driving forces behind bond yields.

REFERENCES

Altavilla, C., Giannone, D., & Lenza, M. (2013). The Financial and Macroeconomic Effects of OMT Announcements. Journal of Money, Credit, and Banking.

Ang, R. (1997). The Intelligent Guide to Indonesia Capital Market, First Edition. Mediasoft Indonesia.

Cochrane, J. H. (2018). The New-Keynesian Liquidity Trap. Journal of Monetary Economics, 92, 47-63.

Christiano, L. J., Eichenbaum, M. S., & Trabandt, M. (2015). Understanding the Great Recession. American Economic Journal: Macroeconomics, 7(1), 110-167.

Del Negro, M., Giannoni, M. P., & Patterson, C. (2020). The Forward Guidance Puzzle. Federal Reserve Bank of New York Staff Reports, 574.

Eertman, M. A. H. (2018). Predicting bond returns using the output gap in expansions and recessions. Econometrie. Retrieved from http://hdl.handle.net/2105/43786.

Gadanecz, B., Miyajima, K., & Shu, C. (2018). Emerging market local currency bonds: Diversification and stability. Emerging Markets Review.

Gali, J. (2020). The Effects of a Money-Financed Fiscal Stimulus. Journal of Monetary Economics, 115, 1-19.

Ghouse, G., Khan, S. A., & Rehman, A. U. (2018). ARDL model as a remedy for spurious regression: problems, performance and prospectus. MPRA Paper. Retrieved from http://ideas.repec.org/p/pra/mprapa/83973.html.

Harris, R. (1995). Cointegration Analysis in Econometric Modelling. New York: Prentice Hall.

Hartono, J. (2009). Teori Portofolio dan Analisis Investasi (Ed. 6). Yogyakarta: BPFE Yogyakarta.

Hofmann, B., Shim, I., & Shin, H. S. (2020). Bond Risk Premia and The Exchange Rate. Journal of Money, Credit, and Banking, 52(S2), 497–520. https://doi.org/10.1111/jmcb.12760.

Hofmann, B., Sufian, F., & Anwar, Z. (2020). Exchange Rate Dynamics and Bond Yields in Emerging Markets. Global Finance Journal.

Hsing, Y. (2015). Determinants of the Government Bond Yield in Spain: A Loanable Funds Model. International Journal of Financial Studies, 3(3), 342–350. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijfs3030342.

Jorda, O., Schularick, M., & Taylor, A. M. (2020). Macrofinancial History and the New Business Cycle Facts. NBER Macroeconomics Annual, 34, 213-238.

Kripfganz, S., & Schneider, D. C. (2023). ardl: Estimating autoregressive distributed lag and equilibrium correction models. The Stata Journal Promoting Communications on Statistics and Stata, 23(4), 983–1019. https://doi.org/10.1177/1536867×231212434.

Kurniasih, A., & Restika, Y. (2015). The influence of Macroeconomic Indicators and Foreign Ownership on Government Bond Yields: A Case of Indonesia. Mediterranean Journal of Social Sciences. https://doi.org/10.5901/mjss.2015.v6n5s5p34.

Kusriyanto, D., & Nelmida. (2019). The Impact of Interest Rate, Inflation Rate, Time to Maturity and Bond Rating: Indonesia Case. International Journal of Economics, Business, and Entrepreneurship, 2(1), 27–40. https://doi.org/10.23960/ijebe.v2i1.52.

Kusumaningrum, D., Anggraeni, L., & Andati, T. (2019). The Effect of Bond Characteristics, Financial Performance and Macro Variables on Return of Corporate Bond in The Agribusiness Sector. Jurnal Manajemen Dan Agribisnis, 16(3), 170-178. https://doi.org/10.17358/jma.16.3.170.

Ludvigson, S. C., & Ng, S. (2009). Macro Factors in Bond Risk Premia. Review of Financial Studies, 22(12), 5027–5067. https://doi.org/10.1093/rfs/hhp081.

Mahirun, M., Fuadah, S., & Jannati, A. (2023). The Influence Of The BI Rate, Inflation, And Gross Domestic Product On Bond Yields [Paper presentation]. International Conference On Social Science Humanities And Art, Universitas Pekalongan.

Mahirun, S., Satria, A., & Yuniarti, E. (2023). Monetary Policy Transmission Through Interest Rate Channels in Indonesia. Economic Modelling.

Malkiel, B. G. (1962). Expectations, Bond Prices, and the Term Structure of Interest Rates. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 76(2), 197. https://doi.org/10.2307/1880816.

Mishkin, F. S. (2019). Economics of Money, Banking, and Financial Markets (12th ed.). Pearson.

Nakamura, E., & Steinsson, J. (2018). Identification in Macroeconomics. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 32(3), 59-86.

Nurfauziah, N., & Setyarini, A. F. (2004). Analisis Faktor-Faktor yang Mempengaruhi Yield Obligasi Perusahaan: Studi Kasus pada Industri Perbankan dan Industri Finansial. Jurnal Siasat Bisnis, 2(9), 241–256. https://doi.org/10.20885/jsb.vol2.iss9.art6.

Nurwulandari, A. (2021). The Effect of the Bank Indonesia Interest Rate, Exchange Rate, and Bond Rating against Bond Yield: Registered Corporate Bonds Issuing Company on the Indonesia Stock Exchange. International Journal of Science and Society, 3(2), 222–231. https://doi.org/10.200609/ijsoc.v3i2.333.

Pesaran, M. H., Shin, Y., & Smith, R. J. (2001). Bounds testing approaches to the analysis of level relationships. Journal of Applied Econometrics, 16(3), 289–326. https://doi.org/10.1002/jae.616.

Poghosyan, T. (2014). Long-run and short-run determinants of sovereign bond yields in advanced economies. Economic Systems, 38(1), 100–114. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecosys.2013.07.008.

Qisthina, G. F., Achsani, N. A., & Novianti, T. (2022). Determinants of Indonesian Government Bond Yields. Jurnal Aplikasi Bisnis Dan Manajemen, 8(1), 76-85. https://doi.org/10.17358/jabm.8.1.76.

Ramey, V. A. (2016). Macroeconomic Shocks and Their Propagation. Handbook of Macroeconomics, 2, 71-162.

Ślusarczyk, B., Meyer, D., & Neethling, J. (2020). An evaluation of the relationship between government bond yields, exchange rates and other monetary variables: The South African case. Journal of Contemporary Management, 17(2), 523–549. https://doi.org/10.35683/jcm20143.89.

Sundoro, H. S. (2018). Pengaruh Faktor Makro Ekonomi, Faktor Likuiditas Dan Faktor Eksternal Terhadap Yield Obligasi Pemerintah Indonesia. Journal of Business & Applied Management, 11(1), 102–115. https://doi.org/10.30813/jbam.v11i1.1072.

Surya, B. A., & Nasher, T. G. (2011). Analisis pengaruh tingkat suku bunga SBI, exchange rate, ukuran perusahaan, dan debt to equity ratio, dan bond rating terhadap yield Obligasi Korporasi di Indonesia. Jurnal Manajemen Teknologi, 10(2), 186-195.

Yuliana, D. (2016). Pengaruh Bi Rate, Inflasi Dan Pertumbuhan Pendapatan Domestik Bruto (PDB) Terhadap Yield Surat Utang Negara (SUN) Periode 2010:07-2015:12. Jurnal Ilmiah Mahasiswa FEB, 4(2), 1–11. https://jimfeb.ub.ac.id/index.php/jimfeb/article/download/2939/2630.

Yusuf, A., & Prasetyo, A. D. (2019). The effect of inflation, US bond yield, and exchange rate on Indonesia bond yield. Jurnal Perspektif Pembiayaan Dan Pembangunan Daerah, 6(6), 649–656. https://doi.org/10.22437/ppd.v6i6.6853.

Zhou, S. (2021). Macroeconomic determinants of long-term sovereign bond yields in South Africa. Cogent Economics & Finance, 9(1). https://doi.org/10.1080/23322039.2021.1929678.