Authors: Ghifari Aprizal dan Annisa Fathonah Sholekah

Since the October 7 attack, Palestinians have woken up to a different world. The genocide has killed at least 42,227 (and counting) people, mostly civilians and children (AJLabs, 2023). The conflict between Israel and Palestine has escalated to an unprecedented level, starting from Israel’s pre-October 7 apartheid regime to a genocide level of war crime that led to the application for the call of Benjamim Nyatenahu, Prime Minister of Israel, arrestment by the International Criminal Court (ICC) (International Criminal Court, 2024). This escalation of terror has started the global calls for boycotts against Israeli products, services, and multinational corporations that engage with the Israeli economy. This boycott movement is led by the existing economic resistance organisation known as the Boycott, Divestment, and Sanctions (BDS) Movement, which aims to pressure Israel to be accountable for its actions and to distort the economic system that is continuing the occupation of Palestinian territories. This essay explores the conflict economic factors that influence boycott participation and the impacts of boycotts, focusing on the genocide done by Israel to the people of Palestine.

Background 1967-2024

The Israeli-Palestinian occupation started in the 1967 Six-Day War when Israel stole the West Bank, Gaza Strip, and East Jerusalem. Over the years, the occupation has led to frequent Israeli attacks on Gaza, with airstrikes and ground invasions. These attacks are aimed at removing Hamas, Palestine’s militant political party which attacked Israel on October 7, but consequently caused the death of many civilians. These attacks perpetuate the cycle of a humanitarian crisis, with Palestinians enduring restrictions on movement in and out of the country, and limited trade and development which cause severe economic instability, with an annual GDP growth rate of 1.0% average from 2000-2024 (CEIC, 2024). If we dig deeper into the individual level, the instability of Palestinian economics shows that in 2006 unemployment rates stayed between 20 and 38 per cent, the GDP per capita was 40 per cent lower than it was in 1999, and poverty rates reached 82 per cent in the Gaza Strip. Additionally, because of this severe economic state, the Palestinian workers provided cheap labour to Israel: in the 1990s 30-40 percent of Palestinian workers were used as cheap and disposable labour in Israel (Farkash, L., 2016).

Meanwhile, Israel has become a developed nation with a technology market. Tech giants like Microsoft house their R&D centre in Tel Aviv. Israel’s economy grew fast because of massive foreign investments in the technological sector, with an annual GDP growth rate of 4.3% average from 1996-2022 (CEIC, 2022)

The stark difference between both states, sharing the same land, could be seen by the difference in GDP and how this occupation only benefits Israel.

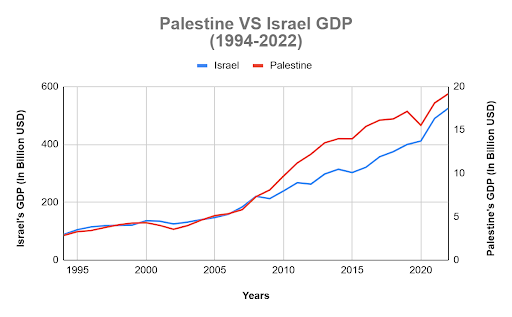

Figure 1.1 Palestine VS Israel GDP (1994-2022)

Source: Palestinian Central Bureau of Statistics & International Monetary Fund (2021)

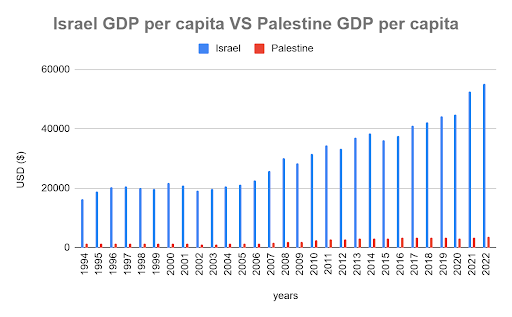

Figure 1.2 Palestine (West Bank & Gaza) VS Israel GDP per capita (2004-2022)

Source: International Monetary Fund (2021)

In Figure 1.1 the graph compares the GDP and GDP growth of Israel and Palestine from 1994 to 2022. The left y-axis represents Israel’s GDP in billions of USD, with a range scale of up to 600 billion, meanwhile, the right y-axis represents Palestine’s GDP in billions of USD, with a range of scale up to 20 billion. From this graph, we can analyse two things:

- Even though both states share the same land geographically the gap between the two states is significant, Israel’s economy is much larger and grows at a more stable pace. Israel’s economy is more stable than Palestine’s due to restrictions put upon Palestine. This shows how prolonged conflict halts economic development for Palestine while allowing Israel to grow its economy.

- Palestine’s dependency on foreign aid might influence the fluctuations because foreign aid can be inconsistent. People perceive that giving aid to the Palestinians will only result in positive results. However several results said otherwise that the aid for Palestine has continued Israel’s occupation of Palestinian territories, undermined Palestinian self-determination, and failed to foster sustainable peace. The current approach does not support the creation of a viable Palestinian state or improve security. This failure underscores the need for a new, more comprehensive and justice-oriented approach to achieving true peace (Ghanem, 2020; LE MORE, 2005 ). Furthermore, frequent attacks done by Israel may also impact the slow growth of Palestine’s economy.

In Figure 1.2, the graph compares the GDP per capita of Israel and Palestine from 1994 to 2022. The blue bars represent Israel’s GDP per capita, while the red bars represent Palestine’s GDP per capita. Israel’s bars dominate the graph, while Palestine’s bars are miniscule compared to Israel’s bars. The significant difference between the two states shows the disparities between the occupier and the occupied. From this graph, we can analyse two things:

- A high GDP per capita, as seen in Israel, correlates with better access to healthcare, education, and infrastructure. Furthermore, disparity in economic resources will affect employment and a better life in general. In contrast, Palestine’s lower GDP per capita correlates with a poor access to economic resources.

- Living in a lower GDP per capita state correlates with living with a lower standard of living, which has a bad social impact and bad psychological effects. Additionally, restrictions and blockades will further worsen the standard of living. This economic hardship will further perpetuate the cycle of poverty and unrest.

The occupation has left Palestine territories with limited land and resources, this occupation is similar to the South African Apartheid’s Bantustans–10 disconnected ”autonomous“ states in the Apartheid regime, where the majority black population separated from the white population. Bantustan could not independently survive as a state because the land was not good for agriculture, therefore its economy depended on the white South Africa’s Economy (South African History Online, 2011). This similarity is important to analyse because both Palestine and Bantustan territories are similar, as they are both fragmented with few resources. The Palestinian economy, especially in Gaza, like Bantustan is severely slowed down by blockades and restrictions such as movement and trade restrictions, military checkpoints and control over infrastructure and resources. These blockades are forcing the people in Gaza to rely on limited local resources and smuggled goods from Egypt for basic supplies, creating economic havoc.

How war affecting Palestine and Israel’s economic growth

From 1994 to 2022, Palestine’s GDP is far lower than Israel’s. In 2022 the GDP of Israel reached around $525 billion, whereas Palestina was far behind at $19 billion. The war between Israel and Palestine has deepened the economic condition between these two countries. According to the Palestine Economic Policy Research Institute (MAS) (2024), the economic conditions in Palestine are detailed below:

- The private sector faced significant setbacks, with an estimated $1.5bn production loss in October and November 2023.

- Gaza grapples with severe food scarcity, with 59% facing emergency or famine conditions, expected to rise to 79% by February 2024. Agricultural value added plummeted by 93% in Q4 2023.

- The tourism sector suffers $2.5M in daily losses, with widespread hotel closures and extensive booking cancellations until December 2024.

- The poverty rate has surged to 58.4 per cent (United Nations, 2024).

In contrast, Israel’s economy shows a substantial rise compared to Palestine. Figure 1.1 demonstrates that Israel’s GDP is mostly supported by the service sector, which contributes to 79% of the GDP. Industry, including construction, accounts for 20%, and agriculture is only contributing to 1% of GDP (United Nations Economic Commission for Europe, 2021). According to Tian et al. (2023), Israel’s military expenditures in 2022 reached $23.4 billion, representing about 4.5% of its GDP. Furthermore, between 1946 and 2023, Israel got a large amount of foreign aid from the USA, for about $263 billion, which makes Israel the biggest recipient of the aid category, especially in military aid. In 2023, the US gave more than $3.8 billion in aid to Israel; the US has contributed around $124 billion from 1946 to 2023 (AJLabs, 2023b).

According to Arafeh (2023) Between 1967 and 1990, 35-40 % of Palestinian labour were forced to work in Israel in low-paid jobs. Palestinian labour was very important to Israel’s economic growth. However, after the Second Intifada, the Israeli government restricted the job for the Palestinians. This brings difficulties not only for the Palestinians but also for Israel. The war in Gaza has created several negative impacts on Israel’s economic future. Such as a reduction in consumption, trade and investment, and a decrease in Israel’s Fitch credit rating from A+ to A due to the costs of war and increased geopolitical risks in Israel. Moreover, Israel is predicted to make additional military expenditures because of the increased tension with Iran. Several main reasons are believed to be the main reason for the decrease in Israel’s economic condition. Those factors are :

- Decline in GDP at the end of 2023 of 20.7%,

- A labour shortage due to limited access to Palestinian workers

- A decline in tourism weakened Israel’s economic situation (Kozul-Wright, 2024).

This war has caused 46.000 small businesses to close since the start of the war on Gaza on 7 October. The word ‘small business’ here refers to a business with up to 5 employees (The New Arab, 2024).

Because of the war, a few countries such as Turkey, Columbia, South Africa, Bahrain, Chile, Honduras, Chad and Jordan cut their diplomatic ties with Israel yet the cutting of trade agreements between those countries and Israel has not been announced. Until this essay is written there is no news that any countries cut their trade deals with Israel. According to Biran et al. (2024), there was a 35% decline in the number of foreign investment entities in the third quarter of 2024 compared to the second quarter, with a similar decline in the number of Israeli investment entities. When comparing the third quarter of this year to the same period last year, there was a decrease of 48% in the number of both Israeli and foreign investment entities. This decline occurred in hi-tech companies, however, it must be noted that hi-tech companies in Israel only contributed around 20% of Israel’s GDP.

Comparing the economic situation that happened to these two countries, especially after the war in 2023 broke out, we can see that although there are some setbacks that Israel has to overcome in its technology sector, the overall condition of its economics is far more promising than Palestinian which has to tackle the challenge of food scarcity for most of its citizen before even talking about recovering its already far left behind economics condition from Israel.

The BDS Movement and Its Economic Goals

The Boycott, Divestment, and Sanctions (BDS) Movement was founded in 2005 to fight against Israel’s occupation of Palestine with a boycott movement, however, their popularity started after the October 7 attack (Al Jazeera, 2024). The BDS movement uses the form of boycott that has long been used as nonviolent resistance to pressure an oppressive system and to demand three things: ending Israel’s occupation, recognising equal rights for Palestinian citizens, and respecting the right of return for Palestinians to their land. From the Montgomery Bus Boycott in the United States to the anti-apartheid boycotts in South Africa, both systems were fixed in December 1965 and May 1990, respectively. History has proven that boycotts have the power to fix an unjust system.

Economic Impact of the BDS Movement

The BDS movement has targeted multinational corporations that have been accused of supporting Israel occupation, such as McDonald’s, Starbucks, and many more. One famous target was McDonald’s with a 60% share of the burger chain share in Israel (Future of Jewish, 2023). After the October 7 attack, McDonald’s franchisees posted on social media that they donated meals to IDF soldiers (Jemma Demosy, 2024). This post went viral and people around the world started being aware of the BDS movement and started boycotting.

Figure 2.1

Source: BDS movement (2024)

This example shows the power of organised boycotts to influence corporate decisions. The BDS movement has not only been pressured to reconsider supporting Israel but has also been encouraged toward supporting local products in various countries, as seen in Indonesia. The boycott of international brands such as PT Unilever, PT Danone, and PT P&G has increased the demand for local brands such as PT KAO, PT Lionwings and PT Indofood. The demand for local producers increases by 30-40%. This shift reduces the dependence on imported goods, strengthening the local Industry (Sinta Dewi Laksmi Santosa, 2024). This example is supported by the principle of substitution, the principle suggests that reducing foreign goods will boost domestic industries.

However, the impact of the boycott has only dented the sales of multinational companies by a small marginal percentage. For example, McDonald’s sales grew by 4% instead of 8% like in the previous quarter (Sam Gruet, 2024). This small impact will not likely cause multinational companies like McDonald’s to pull out of Israel.

Boycott Impact on Pro-Palestine Companies and Pro-Israel Companies

For pro-Israel writers find the BDS movement will not make the multinational company stop their operations and aid Israel. Therefore the purpose of the boycott movement, which is to put pressure on Israel to comply with international law and to persuade private companies to end their participation in Israel’s crimes, has not achieved the results it desired. It only dented the sales of multinational companies by a small marginal percentage (Sam Gruet, 2024).

On the other hand, the writers find that for pro-Palestine companies such as Huda Beauty, there is not enough data to draw any conclusion of whether there was any increase or decrease in product sales, after the owner, Huda Kattan declared her support for Palestine. However, the owner states that she lost some of her contract to be an ambassador.

From this phenomenon, we believe that the party that gets the benefits of the declining sales of the boycott of multinational companies’ products that people perceived as Israel’s supporters, is not the Palestinian-based companies or pro-Palestine companies but rather the local companies where the support of the boycott movement occurred .We conclude that this boycott of companies that people perceive as Israel’s supporters is still in the phase of a symbolic act against Israel rather than a conscious act to directly support Palestinian economics.

Conclusion

The long conflict between Israel and Palestine, especially after the recent October 7 attack, has shown severe economic and social problems, such as Palestine’s struggles with poverty and dependency because of restrictions imposed by the zionist regime, while Israel’s economy has grown, supported by foreign investments ranging from tech development to large military aid. The Boycott, Divestment, and Sanctions (BDS) Movement, a nonviolent resistance effort, has pressured Israel’s economy by targeting global companies that support the occupation. Although the impact of the movement has proven insignificant on a global scale, it has boosted local markets in some BDS-supporting countries. In countries like Indonesia, more people are substituting international brands that are accused of being in support of the occupation for local brands, therefore the movement is helping the countries who are in support of the BDS movement. Thus, while direct economic consequences are limited, the movement has brought global attention to the structural inequities in this genocide.

References

AJLabs. (2023a, October 9). Israel-Hamas War in Maps and charts: Live Tracker. Al Jazeera. https://www.aljazeera.com/news/longform/2023/10/9/israel-hamas-war-in-maps-and-charts-live-tracker

AJLabs. (2023b, October 11). How big is Israel’s military and how much funding does it get from the US? Al Jazeera. https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2023/10/11/how-big-is-israels-military-and-how-much-funding-does-it-get-from-the-us

Arafeh, N. (2023, November 15). Palestine’s Disposable Laborers. Carnegieendowment.org. https://carnegieendowment.org/middle-east/diwan/2023/11/palestines-disposable-laborers?lang=en

Biran, D., Patir, A., Grisariu, A., & Mekonen, T. (2024, October 6). The State of Israeli High-Tech In the Shadow of a Year of War – SNPI. SNPI. https://rise-il.org/insight/the-state-of-israeli-high-tech-in-the-shadow-of-a-year-of-war/

CEICdata.com. (2020). Palestinian Territory Real GDP Growth. Ceicdata.com; CEICdata.com. https://www.ceicdata.com/en/indicator/palestinian-territory-occupied/real-gdp-growth

Dempsey, J. (2024, April 4). McDonald’s to buy back Israeli restaurants after boycotts. Www.bbc.com. https://www.bbc.com/news/business-68735706

Dessus, S. (2004). A Palestinian Growth History, 1968-2000. Journal of Economic Integration, 19(3), 447–469.

Farsakh, L. (2016). Palestinian Economic Development: Paradigm Shifts since the First Intifada. Journal of Palestine Studies, 45(2), 55–71. https://doi.org/10.1525/jps.2016.45.2.55

Fickenscher, L. (2023, October 18). Huda Beauty faces boycott calls after founder Huda Kattan spurns “blood money” from Israeli customers. New York Post. https://nypost.com/2023/10/18/huda-beauty-faces-boycott-calls-after-founder-huda-kattan-spurns-blood-money-from-israeli-customers/

Firstpost. (2024, May 3). After Colombia, now Turkey: Which other nations have cut ties with Israel over Gaza war? Firstpost. https://www.firstpost.com/explainers/colombia-turkey-nations-israel-gaza-war-13766667.html

Future of Jewish. (2023, August 10). When Israel Started a Food Fight With McDonald’s. Futureofjewish.com; Future of Jewish. https://www.futureofjewish.com/p/when-israel-started-a-food-fight#footnote-1-135848690

Ghanem, A. (2020). The Impact of Incentives for Reconciliation in the Holy City – How International Aid for the Palestinians Contributed to the Expanding of Israeli Control over East Jerusalem. Defence and Peace Economics, 31(8), 975–989. https://doi.org/10.1080/10242694.2020.1762315

Hever, S. (2024, July 19). The end of Israel’s economy. Mondoweiss. https://mondoweiss.net/2024/07/the-end-of-israels-economy/

Instagram. (n.d.). https://www.instagram.com/p/C1u_OvWsPpR/?igsh=MXN2ZmJlZ21vaXF3bg==

International Criminal Court. (2024). Statement of ICC Prosecutor Karim A.A. Khan KC: Applications for arrest warrants in the situation in the State of Palestine. International Criminal Court. https://www.icc-cpi.int/news/statement-icc-prosecutor-karim-aa-khan-kc-applications-arrest-warrants-situation-state

International Monetary Fund. (2021a). Israel GDP, current prices (Billions of U.S. dollars). Www.imf.org. https://www.imf.org/external/datamapper/NGDPD@WEO/ISR?zoom=ISR&highlight=ISR

International Monetary Fund. (2021b). Israel GDP per capita, current prices (U.S. dollars per capita). Imf.org. https://www.imf.org/external/datamapper/NGDPDPC@WEO/ISR?zoom=ISR&highlight=ISR

International Monetary Fund. (2021c). West Bank & Gaza GDP per capita, current prices (U.S. dollars per capita). Www.imf.org. https://www.imf.org/external/datamapper/NGDPDPC@WEO/WBG?zoom=WBG&highlight=WBG

PCBS. (2021). PCBS | Major national accounts variables in Palestine* for the years 2021, 2022at current prices. Pcbs.gov.ps. https://www.pcbs.gov.ps/statisticsIndicatorsTables.aspx?lang=en&table_id=2243

Kozul-Wright, A. (2024, August 23). Gaza war extends toll on Israel’s economy. Al Jazeera; Al Jazeera. https://www.aljazeera.com/economy/2024/8/23/gaza-war-extends-toll-on-israels-economy

LE MORE, A. (2005). Killing with kindness: funding the demise of a Palestinian state. International Affairs, 81(5), 981–999. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2346.2005.00498.x

Palestinian BDS National Committee . (2016, May 8). Economic Boycott. BDS Movement. https://bdsmovement.net/economic-boycott

Palestinian Central Bureau of Statistics. (2024, October 26). PCBS. Www.pcbs.gov.ps. https://www.pcbs.gov.ps/default.aspx

Sinta Dewi Laksmi Santosa. (2024). THE IMPACT OF THE BOYCOTT OF ISRAELI PRODUCTS, BRANDS AND THEIR SUPPORTERS ON THE INDONESIAN ECONOMY. Jurnal Ilmu Ekonomi Dan Pembangunan, 24(1), 7–7. https://doi.org/10.20961/jiep.v24i1.82042

South African History Online. (2018, March 16). The Homelands. South African History Online. https://www.sahistory.org.za/article/homelands

The New Arab. (2024). War on Gaza forces 46,000 Israeli businesses to close. The New Arab. https://www.newarab.com/news/war-gaza-forces-46000-israeli-businesses-close

The Palestine Economic Policy Research Institute (MAS) . (2024). Palestine Economic Update – January 2024. MAS. https://mas.ps/en/publications/9609.html

Tian, N., Silva, D. L. da, Liang, X., Scarazzato, L., Béraud-Sudreau, L., & Assis, A. (2023, April 1). Trends in World Military Expenditure, 2022. SIPRI. https://www.sipri.org/publications/2023/sipri-fact-sheets/trends-world-military-expenditure-2022

United Nations. (2024, May 2). Palestine’s economy in ruins, as Gaza war sets development back two decades | UN News. News.un.org. https://news.un.org/en/story/2024/05/1149261

United Nations Economic Commission for Europe. (2021). ISRAEL – Statistical Database . Unece.org. https://w3.unece.org/CountriesInFigures/en/Home/Index?countryCode=376